Suing Cops for Acts of Violence Leads to Better Policing But Doesn't Stop the System of White Supremacy, the cause of police brutality

The Center for Justice and Democracy has just released an interesting and timely fact sheet – “Fact Sheet: Civil Lawsuits Lead to Better Safer Law Enforcement,” that shows that suing the police for acts of violence leads to better policing. The fact sheet contains a number of cases where “[lawsuits have] had a direct and positive impact on law enforcement, with settlements in individual cases leading to better training, safer policies and overall better practices.”

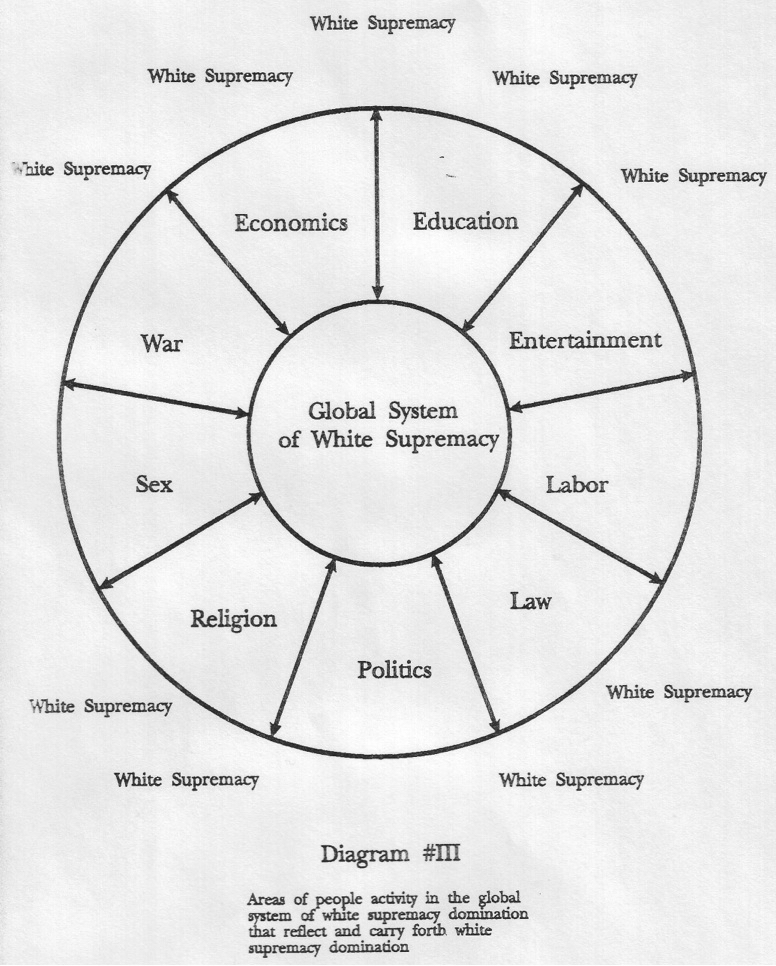

It is a good example of the ways that the tort system, and trial by jury benefits, not merely for the injured victim, but all of us. Unfortunately, as the fact sheet points out, “each case would be essentially barred by current legislation in Congress that would make it nearly impossible to sue the police, no matter how severe the constitutional violation.” [MORE] Nevertheless, the genocidal murder or justifiable homicide of non-whites, particularly Black males is major tool of the system of white supremacy/racism. [MORE]

From [CJ&D] As many recent examples show, the filing of criminal charges against police officers for excessive use of force is exceedingly rare, and even if charges are brought, juries are loath to convict them.[1] It is clear that if systemic problems have afflicted a police department’s use of force policies, criminal prosecutions may not be the best way to correct them.

On the other hand, successful civil lawsuits filed by victims have been a critical tool for police departments to identify and remedy potentially widespread abuses. As UCLA law professor Joanna C. Schwartz, a leading expert in police misconduct litigation, wrote in 2011,[2]

[A] small but growing group of police departments around the country have found innovative ways to analyze information gathered from lawsuits. They investigate lawsuit claims as they would civilian complaints, and they discipline, retrain or fire officers when the claims are substantiated. They look for trends in lawsuits suggesting problem officers, units and practices, and they review the evidence developed in the cases for personnel and policy lessons.

Indeed, lawsuits can have a direct and positive impact on law enforcement, with settlements in individual cases leading to better training, safer policies and overall better practices. The following are examples of recent cases that have had such a constructive result. Notably, each case would be essentially barred by current legislation in Congress that would make it nearly impossible to sue the police, no matter how severe the constitutional violation.[Each case would be essentially blocked by the “Back the Blue Act of 2017,” which provides, “if the police can show that the violation and resulting injuries were ‘incurred in the course of, or as a result of, or…related to, conduct by the injured party that, more likely than not, constituted a felony or a crime of violence…(including any deprivation in the course of arrest or apprehension for, or the investigation, prosecution, or adjudication of, such an offense),’ then the officers are liable only for out-of-pocket expenses. What’s more, the bill would bar plaintiffs from recovering attorneys fees in such cases.” Radley Balko, “A new GOP bill would make it virtually impossible to sue the police,” Washington Post, May 24, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-watch/wp/2017/05/24/a-new-gop-bill-would-make-it-virtually-impossible-to-sue-the-police/]

Excessive force ended in death

Jeremy McDole, 28 and paralyzed from the waist down, was shot to death by four police officers on September 23, 2015 while sitting in his wheelchair. The officers had confronted McDole after receiving a 911 call about a man with a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Bystander video showed an officer pointing a gun at McDole, screaming at him to drop his gun and put his hands up and then firing a shot at McDole when he started fidgeting in his chair and moving his hands toward his waist. According to a Delaware Department of Justice Report, the footage also clearly showed that “(1) Mr. McDole’s hands were on the arms of his wheelchair when he was shot, and (2) [the officer] gave Mr. McDole two commands to ‘show me your hands’ in the space of approximately two seconds before he discharged his shotgun,” an act that “fundamentally changed the dynamic of the incident involving Mr. McDole.” Less than one minute after the initial shot was fired, three other officers shot McDole 15 times, killing him.[4]

In March 2016, McDole’s family filed a civil lawsuit against the city of Wilmington and its police department, alleging that the officers had violated “use of force” policies, had no justification for such “grossly excessive and wanton lethal force” and that the shooting was racially motivated.[5]

Nine months later, the case settled for $1.5 million. As part of the agreement, Wilmington police pledged to evaluate its current de-escalation tactics and officer training and “consider a comprehensive use of force policy that will outline when force is appropriate and train officers in de-escalation procedures.” In early March 2017 – three months after the settlement was announced – the police chief met with McDole’s family and stated that Wilmington police would adopt an objective use of force standard and annually undergo training in how to deal with mental health encounters, use of force and de-escalation.[6]

Traffic stop ended in death

Darius Pinex, a 27-year-old father of three, was shot to death during a January 7, 2011 traffic stop in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood. According to the officers, they stopped Pinex’s car with their guns drawn after hearing an emergency radio alert about a similar vehicle connected to a shooting. They claimed that this dispatch plus Pinex’s actions – namely refusing orders, driving in reverse and accelerating forward – justified opening fire on his car and shooting him in the head.[7]

In June 2012, Pinex’s family filed a federal civil lawsuit against Chicago and the two officers, alleging excessive force in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 as well as various civil rights violations under Illinois state law.[8] More specifically, they argued that “the officers aggressively cut off Pinex’s car, rushed out with guns drawn and pointed, all the while screaming at [them]” and then “fired an initial shot without reason, provoking Pinex into fleeing.”[9]

During discovery, Pinex’s family was led to believe there was no recording of the emergency dispatch or any documents related to the recording. However, the judge learned mid-jury trial that: 1) the city attorney had found a recording of the actual alert the officers heard before the stop; 2) the actual alert contradicted the officers’ story about an emergency call connecting a car like Pinex’s to an earlier shooting; and 3) the city attorney had uncovered the actual alert a week before trial.[10]

In a January 2016 opinion, the judge chastised the city attorney for intentionally withholding this crucial piece of evidence, criticized another city attorney for failing to make a reasonable effort to find that evidence and ordered a new trial. Widespread publicity about the ruling prompted the city’s Federal Civil Rights Litigation (FCRL) Division to announce greater transparency regarding active cases. In addition, the mayor’s corporation counsel “instituted several new procedures, including a policy that drastically reduces the Police Department’s role in collecting documents for litigation.” And within days of the decision, Chicago’s mayor hired a former U.S. attorney to conduct an extensive review of the FCRL department; that six-month inquiry resulted in over 50 recommendations of reforms. The case ultimately settled for $2.34 million in December 2016.[11]

Police encounter resulted in death

On April 26, 2014, preschool teacher Samantha Ramsey, 19, was shot to death by a Boone County sheriff’s deputy while driving away from a large outdoor party along the Ohio River. The officer had jumped on the hood of Ramsey’s car when she allegedly began to speed off instead of stopping for a sobriety check. The officer then pulled out his gun and shot Ramsey four times through the windshield, later telling investigators that he thought he would be killed. The officer was never charged or disciplined.[12]

Ramsey’s family – in addition to three passengers, who claimed to be held at gunpoint as they exited the car after it rolled backward into a ditch – filed a civil rights and wrongful death lawsuit against Boone County, its sheriff’s office and the deputy.[13] According to the complaint, “Without any warning to Ms. Ramsey or her passengers, [the officer] jumped onto the hood of Ms. Ramsey’s car and demanded that she stop the vehicle,” and “[a]s Ms. Ramsey was stopping the car [the officer] fired his weapon four times through the windshield. He killed Ms. Ramsey and terrorized her three passengers.”[14]

Discovery revealed, among other things, that: 1) “Boone County conducted an investigation not designed to determine what really happened”; 2) all members of a four-officer panel reviewing the County’s investigation of the killing had agreed that if the officer “had let the car just go, the situation wouldn’t have happened” and that, instead of shooting Ramsey, he could have “followed in his cruiser or could’ve taken down plate information and radioed colleagues to stop her”; and 3) the sheriff’s deputy might have been on Xanax the night of the shooting.[15]

In December 2016, the case settled for $3.5 million. Under the agreement, the sheriff’s office pledged to revise its use of force policy, create clearer guidance on officers’ use of prescription medication while on duty, have patrol officers wear body cameras by the end of 2017 and involve a police practices expert to help ensure that such reforms are implemented. “I’m pleased with the changes the county’s willing to make,” Ramsey’s mother said. “It will protect the citizens, as well as the sheriff’s deputies.”[16]

Use of excessive force resulted in death

Jaime Reyes, 28-years-old, died on June 6, 2012 after being shot multiple times in the back by a Fresno, CA police officer. Reyes, on meth, had run away from police; an officer shot him as he neared the top of a fence and then three more times in the back as he lay face down on the ground. He was frisked, handcuffed and later provided with medical assistance, ultimately dying at the hospital after failed emergency surgery. Less than a year later, Reyes’ parents filed a wrongful death action against the City of Fresno, its police chief and officers from the Fresno Police Department. According to the complaint, Reyes never had anything in his hands, never threatened the officers and was more than five yards ahead of the officer when he was first shot. It was only as he lay motionless from the three additional shots that officers found an unloaded gun wrapped in a plastic bag in his shorts pocket.[17]

In November 2016, the case settled for $2.2 million. As part of the settlement, the Fresno Police Department agreed to: 1) change its use of-force policy; 2) train sergeants and patrol officers not to fire extra bullets unnecessarily; and 3) train homicide detectives and police Internal Affairs officers to consider witness statements that conflict with accounts by officers at the scene.[18]

Use of excessive force resulted in death

On October 11, 2012, U.S. Navy veteran Kenny Releford, 38, was shot to death by a Houston police officer as he stood unarmed in the middle of the street. Releford’s friend had called police for help after Releford, who suffered from schizophrenia, broke into the friend’s home during a mental health crisis. No one in the house had been injured, and Releford went home after the incident. When the officer arrived, he ordered Releford outside with his patrol loudspeaker; Releford complied and began approaching the officer as instructed. Multiple eyewitnesses testified through affidavits that: 1) Releford’s hands were clearly visible and unarmed when the officer shot him; and 2) the officer shot Releford again as he tried to get up from the street.[19]

Two years later, Releford’s father filed a federal lawsuit, alleging that the officer had “violated Kenny’s constitutional rights by using excessive force against him” and that the City of Houston had “violated Kenny’s constitutional rights by failing to properly supervise, train, discipline, or investigate its officers in the use of force and by adopting a custom or policy that caused Kenny’s death in violation of his constitutional rights.”[20] He argued that that Houston Police Department officials “repeatedly improperly cleared officers who’d shot or killed unarmed people — even when the department's own internal affairs investigations revealed violations of training, policies or state law.[21] In June 2017, the case settled for $260,000.

As reported by the Houston Chronicle, “Because of rulings in the case by U.S. District Judge Keith Ellison, the Houston Police Department was compelled to release previously secret internal reviews of Releford’s shooting as well as of other unarmed Houstonians.” These documents publicly confirmed systemic problems for the first time, including information that “contradicted the officer’s account in the fatal shooting of a mentally ill double amputee named Brian Claunch, who was in a wheelchair when an HPD officer shot and killed him in 2012.”[22] Publicity surrounding the lawsuit “boosted public awareness about police use-of-force and weaknesses in HPD’s reviews of officer-involved shootings.”[23]

Restraints caused asphyxiation

Bruce Klobuchar, the 25-year-old son of a former police officer, died in August 1995 after Los Angeles police bound his legs and hands together behind his back. The officers claimed he was under the influence of drugs and causing a disturbance and that they had decided to “hogtie” him because other restraint methods proved ineffective. The county coroner found that restraint contributed to his death.[24]

In February 1996, Klobuchar’s parents filed a lawsuit against the City of Los Angeles and its police department. Discovery showed that dozens of people had died while, or immediately after being hogtied, and that the police department had known for nearly a decade that the restraint procedure could be lethal. The case settled in July 1997, with the city of Los Angeles agreeing to pay Klobuchar’s family $750,000 and ban “hogtying.”[25] [MORE]