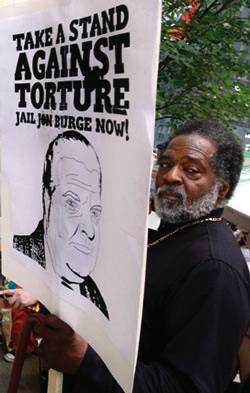

At No Extra Charge Black Men Can be Electrocuted & Beaten for Confessions: Chicago Pays $5.5 Million for Brutality Fund but White Cop Torture Boss Doesn't Owe a Penny! [no accountability for racists in racist system of unequal power]

Sentencing Guidelines Apply to Racist Suspects? Like the recent Wash Post study found, white cops are routinely not punished for brutalizing non-white people. Even when their conduct has resulted in a monetary award of legal damages, cops rarely are held personally liable - they pay nothing, the Government pays. Here, after prosecutors asked for a 30 year jail sentence, Jon Burge was sentenced to only 4. He was then released early after serving only 3 yrs. He is still collecting a $3000 a month pension and the City of Chicago continues to be bound by court order to pay his legal fees. [MORE] In other words, like Donald Sterling who hit the jackpot after his racist episode, Mr. Burge is actually undercover rewarded by other whites for his racist acts.

From [HERE] Whenever white Chicago Police commander Jon Burge needed a confession, he would walk into the interrogation room and set down a little black box, his alleged victims would later tell prosecutors. The box had two wires and a crank. Burge, they alleged, would attach one wire to the suspect’s handcuffed ankles and the other to his manacled hands. Then, they said, Burge would place a plastic bag over the suspect’s head. Finally, he would crank his little black box and listen to the screams of pain as electricity coursed through the suspect’s body.

“When he hit me with the voltage, that’s when I started gritting, crying, hollering. … It [felt] like a thousand needles going through my body,” Anthony Holmes told prosecutors during a 2006 investigation into Burge. “And then after that, it just [felt] like, you know—it [felt] like something just burning me from the inside, and, um, I shook, I gritted, I hollered, then I passed out.”

Holmes, who eventually gave what he says was a false confession and was convicted of murder in 1973, is one of as many as 120 African-American men on Chicago’s South Side who were allegedly tortured by Burge between 1972 and 1991.

Though prosecutors accumulated evidence against Burge they thought “sufficient to establish guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,” the statute of limitations prevented prosecution. Burge instead went to jail for perjury later, for denying his role under oath.

On Tuesday, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced the establishment of a $5.5 million fund for these victims. The compensation would “close this book, the Burge book on the city’s history,” Emanuel said according to the Chicago Tribune. [This simpleton can close whatever is he wants to close.]

But as the country continues to reel from new cases of racial profiling and police brutality, the story of how Burge allegedly became America’s most infamous alleged torturer can’t be consigned to history. It is simply too horrific.

Before Burge was an old man holed up in a Florida retirement home and dogged by his past deeds, he was a wannabe soldier and a college dropout. He grew up on Chicago’s Southeast Side and was active in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), according to the Chicago Reader. He only lasted a semester at the University of Missouri before moving back in with his parents and working as a stock clerk. In 1966, he enlisted in the Army with the idea of eventually becoming a Chicago police officer, the Chicago Reader reported.

“Army records describe the 18-year-old recruit as red-haired, blue-eyed, six feet two inches tall, 210 pounds, a member of the Congregational Church, interested in cars and baseball,” also according to the Chicago Reader. “On June 18, 1968, with antiwar sentiment escalating back home and city officials bracing for what would be a violent Democratic convention, Burge volunteered for Vietnam. He arrived there in November as a sergeant.”

What, exactly, Burge did in Vietnam is a bit of a mystery. In its 2005 profile of Burge, the Chicago Reader suggests Burge may have honed his torture techniques on suspected Vietcong soldiers and sympathizers. Multiple members of Burge’s Ninth Military Police Company told the newspaper that they had either witnessed or heard of interrogations using a “field phone” similar to the black box Burge would later be accused of using. In what they called “the Bell telephone hour,” soldiers would shock prisoners in an attempt to obtain information.

Whatever he did in Vietnam, Burge was honorably discharged in 1969. When he applied to the Chicago Police Department later that year, the officer assigned to do a background check praised Burge as “all man.” Burge was hired in 1970 and was promoted to detective two years later.

That’s when the torture allegedly began.

More than 120 people — mostly African-American men — have accused Burge of shocking, beating or suffocating them into confessing. According to the Chicago Reader, the first known case was Holmes, a body-building gang leader arrested on charges of killing a witness who was set to finger Holmes’s brother-in-law for murder.

Burge took his prisoner to an interrogation room inside Chicago Police’s Area Two headquarters, Holmes later told attorneys. There, Burge took out his black box and attached the wires to Holmes. He put a plastic bag over the suspect’s head. When Holmes bit through it in an attempt to breathe, Burge added another bag. Then he began cranking.

“You going to talk, n—–?” Burge asked as he shocked Holmes. [Nigger is what is being done to you. Nigger means victim of white supremacy.]

Like scores of suspects after him, Holmes broke thanks to the “Bell telephone hour.” He confessed to the crime — a statement he has since recanted — and was sentenced to 75 years in prison. He served 30 years before being released.

Burge and his crew of “midnight detectives” were feted by their superiors for cracking down on violent gangs. One case, in particular, seemed to capture Burge’s role at the Chicago Police Department. It also would lead to his downfall. In 1982, two Chicago police officers pulled over a convicted felon named Andrew Wilson. Wilson had just been paroled after a stint for armed robbery. When the cops approached his car, he stripped one of the officers of his gun and used it to kill both of them, according to the Chicago Reader.

Jon Burge led the manhunt for the cop killer. The police commander personally picked the lock on Wilson’s door and led the arrest — as well as the 15-hour interrogation. Wilson confessed, but later told “public defender Dale Coventry that he’d been shocked, burned by a radiator, suffocated with a plastic bag, and kicked in the eye and beaten,” according to the Chicago Reader. “Coventry had photos of a huge burn on his client’s thigh, parallel burns on his chest, and strange U-shaped puncture marks on his nose and ears. Wilson said the marks came from alligator clips attached to wires leading to a hand-cranked electrical device. He said Burge shocked him on his genitals and his back with a second device that resembled a curling iron.”

Five years later, after he was retried and reconvicted of the murders, Wilson launched a civil suit against Burge for torture. The lawsuit would drag out for a decade, but Wilson would eventually receive a $1.1 million settlement. In the meantime, Wilson’s lawyers began hearing from scores of other men who claimed to have been tortured by the police commander.

One repeated and particularly gruesome allegation was that Burge inserted strange shock devices up suspects’ rectums. Burge’s lawyers said such a device was “nonexistent, unbelievable, unfunctional, unreal.” But the Chicago Reader identified the potential torture device as a “a violet ray machine” or “violet wand” sometimes used in S&M.

Over the past 18 years, the list of alleged victims has swelled to at least 120. Some of the men spent years on Illinois’s death row because of confessions allegedly obtained by Burge under duress. In 2003, Governor George Ryan pardoned four men on death row who claimed to have been tortured by Burge.

Burge’s own career began to fall apart in 1993, when the Chicago Police Board voted to fire him for his alleged torture activities. The police commander was allowed to keep his $4,000 per month pension.

Mounting evidence of torture led to public demands for an indictment against Burge. In 2002, Cook County appointed special prosecutor Edward J. Egan to investigate Burge’s conduct. The investigation took four years and cost $7 million, but the 300-page report didn’t recommend bringing any charges against the former cop. The statute of limitations for the alleged crimes had expired, Egan argued.

Instead, it would take testimony in a civil case to send Burge to prison. The police commander was usually savvy enough to invoke his Fifth Amendment right not to incriminate himself. But during one deposition in 2003, Burge went on the record denying ever torturing anyone. Five years later, prosecutors filed perjury charges against Burge, and in 2010 a federal judge sentenced him to 4½ years in prison.

In October, Burge was allowed to exchange his prison cell for a Florida halfway house. And in February, he was freed altogether. It was a bitter moment for Burge’s victims, some of whom remain behind bars.

“I need some help,” Holmes told the Chicago Tribune at the time of Burge’s release from prison. “I try to hold my emotions back because I don’t want people to see me like that. … My family has been through a lot.”

Yet, Burge’s release also seems to have spurred Chicago city officials to action. Mayor Rahm Emanuel had sat on a $20 million settlement proposal for a year. But on Tuesday, a week after winning reelection, Emanuel said he was ready to endorse a smaller, $5.5 million fund for Burge’s victims. (The city has already spent close to $100 million on legal fees and settlements related to the accusations against Burge, according to USAToday.)

“We are gratified, that after so many years of denial and cover-up by the prior administration, the city has acknowledged the harm inflicted by the torture and recognized the needs of the Burge torture survivors and their families by negotiating this historic reparations agreement,” Joey Mogul, an attorney representing many of Burge’s victims, told USAToday. “This legislation is the first of its kind in this country, and its passage and implementation will go a long way to remove the longstanding stain of police torture from the conscience of the city.”

With police brutality again in the news thanks to a series of police-involved shootings of unarmed African-American men, however, America’s conscience is far from clear. Burge’s little black box may be resigned to history, but racism, apparently, is not.