Uncivilized Authorities in Texas Murder Black Man who Murdered a Black Cop -Jury was Never Instructed to Consider Evidence Supporting a Sentence Less than Death, had an IQ of 65

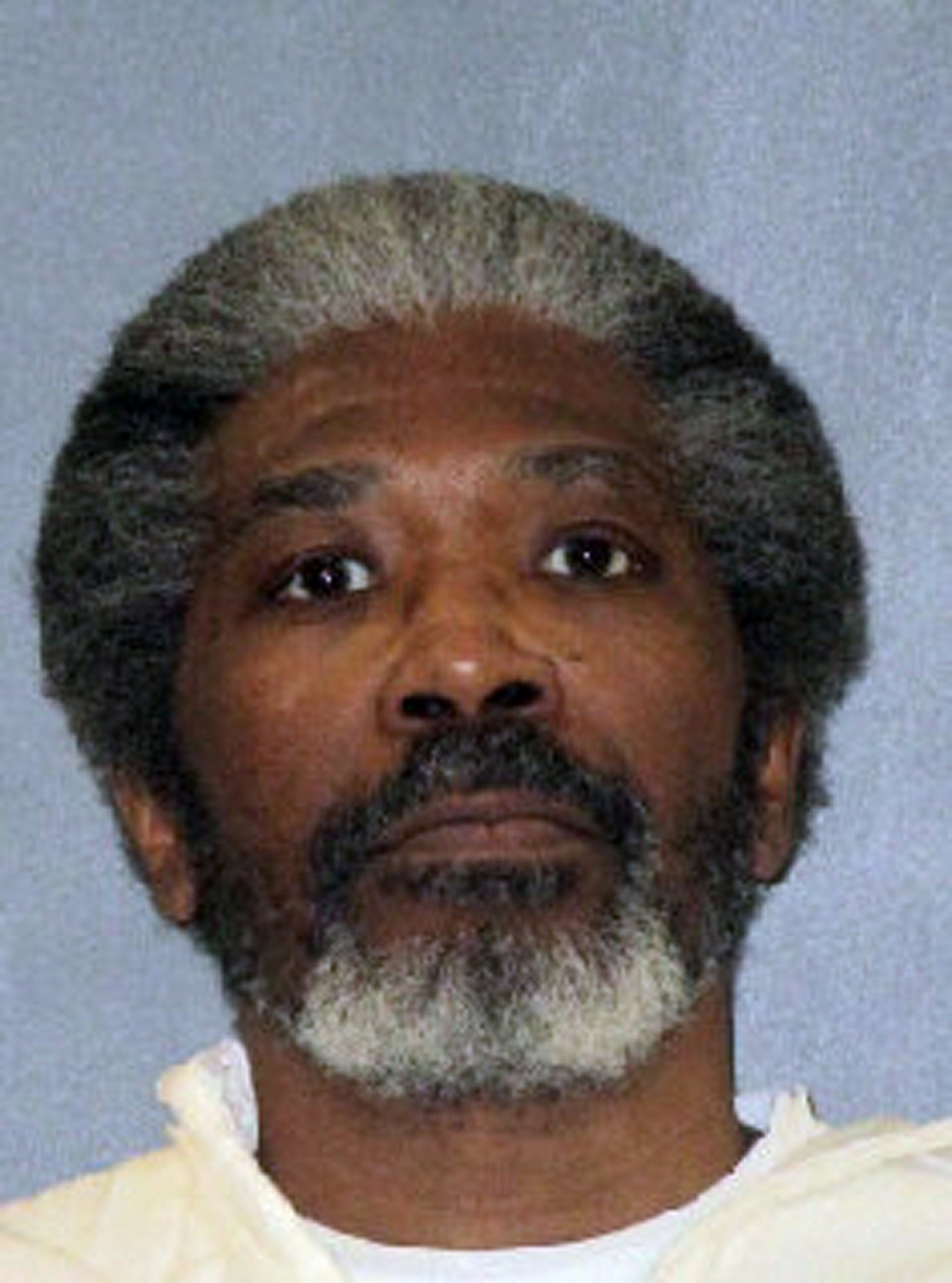

/From [HERE] and [HERE] A 61-year-old Black man was executed Wednesday evening for killing a Black Houston police officer more than three decades ago. He was murdered by Texas amid questions as to his eligibility for capital punishment and the constitutionality of his death sentence.

Jennings was convicted under a sentencing procedure that the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down shortly before his trial in 1989 because it did not adequately allow jurors to consider evidence supporting a sentence less than death.

The jury instructions given in his case to redress that error were also later declared unconstitutional, and 25 Texas death-row prisoners had their death sentences overturned as a result. However, Jennings’s court-appointed trial and appeal lawyers failed to raise the issue in Texas state court and the Texas federal courts refused to consider the issue on the grounds that the state court lawyers had procedurally defaulted the claim. The U.S. Supreme Court later changed federal habeas corpus procedures to permit review if ineffective state-court representation caused the default. But when Jennings’s federal lawyers attempted to raise the issue again, the Texas federal appeals court ruled on January 28 that its prior decision had not been based on procedural default and that it had already rejected the claim. Without comment, the Supreme Court issued an order on January 30 declining to hear Jennings’s case, and he was executed.

Robert Jennings received lethal injection for the July 1988 fatal shooting of Officer Elston Howard during a robbery at an adult bookstore that authorities said was part of a crime spree.

In challenging Jennings’s death sentence, his current lawyers also argued that both Jennings’s trial lawyer and his previous appellate attorney provided inadequate representation. Jennings’s trial attorney was defending two death-penalty cases at the same time and did not investigate significant mitigating evidence that included Jennings’s history of brain damage from a car crash and an injury with a baseball bat, an IQ of 65, and intellectual and adaptive deficits associated with his low IQ. Trial counsel also failed to present readily available evidence of Jennings’s impoverished, abusive, and neglectful upbringing: he was born as the result of a rape, and his mother frequently told him she did not want him. His original appeal lawyers also failed to raise these issues. Edward Mallett, one of Jennings’s current lawyers, said, “There has not been an adequate presentation of his circumstances including mental illness and mental limitations.”

U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes took the unusual step earlier in January of asking the state to consider supporting clemency for Jennings, citing the 30-year delay between the crime and the scheduled execution. Jennings's attorneys argued in his clemency petition that the state had granted clemency last year to a white death-row prisoner with fewer mitigating circumstances. "Denying a commutation truly will demonstrate that race, class, and privilege matter in determining who is executed in Texas," attorney Randy Schaffer wrote. "This would send a terrible message to the world."

As witnesses filed into the death chamber, Jennings asked a chaplain standing next to him if he knew the name of the slain officer. The chaplain didn't respond, and a prison official then told the warden to proceed with the punishment.

"To my friends and family, it was a nice journey," Jennings said in his final statement. "To the family of the police officer, I hope y'all find peace. Be well and be safe and try to enjoy life's moments, because we never get those back."