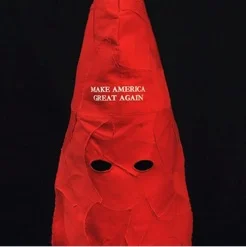

Facebook Bans Political Artist for Posting an Image of a Sculpture Depicting MAGA "Hate Hats" as KKK Hoods

/From [MintPress] Facebook has a longstanding tradition of stifling dissenting and alternative voices, including those of journalists. Now, artists’ careers are being hurt by the strongarm of the social media behemoth.

Earlier this month, artist Kate Kretz — who employs a multitude of techniques, including silverpoint, wood burning, drawing, painting, embroidery and sculpture — had her account disabled for posting images of her latest work.

The offending image was of her recent piece, entitled “Hate Hat,” which resembles the hoods made infamous by the Ku Klux Klan. It’s red and made out of “Make America Great Again” hats (knockoffs, she insists), and features the slogan above the eyes. The provocative display is a clear dig at President Donald Trump, meant to highlight his bigotry.

Kretz’s work wasn’t always political, she says. It wasn’t until eight years ago, when she had a child, that she began to think about the world her daughter would grow up in. She writes:

My practice is now devoted to calling out injustices against disparate parts of our community, investigating overlaps to suggest that, although the victims may change, the perpetrators are often the same. I have named the ongoing series ‘#bullyculture,’ because I believe that the U.S. cultivates aggression and entitlement in a myriad of ways, both overt and subtle.”

Privatizing the public square

The implications of Kretz’s ban from Facebook are many. The First Amendment protects freedom of expression in public. But Facebook and other social media companies have formed monopolies over the world’s most traveled avenues for dialogue. Indeed, the public square has become privatized, and there is little recourse for those silenced as a result.

Kretz’s article on the removal of her Facebook page is worth reading in its entirety: she hits on many issues relating not just to the tech giant but also to the precarious position of artists under capitalism. “All but the top one percent of artists are struggling,” she writes, continuing:

Social media has been a tremendous help in this area: I can create a new work, post it, get instant feedback, and often, within a few weeks or months, get offers to exhibit it. While a few hundred to a few thousand people might see my art ‘in real life’ during the course of an exhibition, a strong, well-photographed image placed on social media can reach ten times as many eyes through multiple ‘shares.’”

An image Kretz altered for Facebook after her first one was removed.

The ease of using Facebook to promote her work has allowed her to balance her passion with a teaching job and mothering of a child. Beyond now losing the ability to share her work, she has also been robbed of an extensive network of supporters she had cultivated over the years. She writes:

My Facebook archive, more extensive than a scrapbook, contains a decade of my artistic creations, exhibitions, reviews, and people’s responses to them, as well as articles and references that have fueled the content of my work, and the shared work of artists I admire. A third of my career history is now owned by someone else and is being withheld from me, the content provider. I feel invisible, like I have been ‘disappeared’ in some nightmarish dystopian novel.”

Regarding the idea of appealing her ban, she notes, “Facebook is an impenetrable fortress, completely disempowering to any user who feels they have been wronged.”

Workarounds to Kafkaesque censorship

Despite the blow to her business, Kretz argues that the real issue is “much bigger” and highlights how Facebook’s community standards have been weaponized against well-meaning people. She notes that a “Dyke March” was canceled on the platform because the term was considered a slur.

There is also the instance of a Facebook event page to coordinate a counter-protest to a demonstration of white supremacists in Washington, celebrating the anniversary of activist Heather Hyer’s murder by neo-Nazi James Fields. The page was shut down days before the event because of supposed Russian infiltration.

For her part, Kretz urges her readers not to self-censor in the face of a Kafkaesque censorship regime. “Instead, find creative workarounds for sharing it.”

For this reason, MintPress News is active on Minds.com, an open-source social-media platform “for internet freedom.”