Value of Black Citizenship Low in CA: Berkeley Study says [white] DA's Removed Blacks from Juries in 72% of the Cases They Examined & 98% of Removal Challenges Lose on Appeal [white judges]

/Trial By an Unlawfully Created State Body [a jury]. There are only a few ways that Americans can meaningfully exercise their citizenship; enlisting in the military, running for national office, voting and serving on a jury. Like voting, jury service is a basic right of citizenship THAT IS AN ILLUSORY FOR BLACK CITIZENS. [MORE]

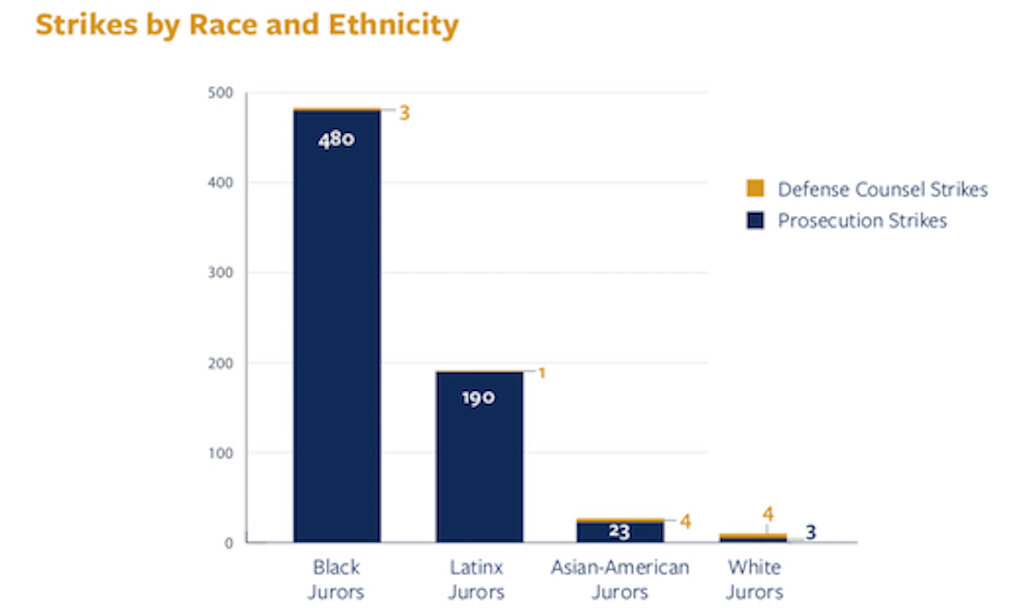

From [HERE] “Prosecutors continue to exercise peremptory challenges to remove African Americans and Latinx people from California juries for reasons that are explicitly or implicitly related to racial stereotypes,” according to a study by the Berkeley Law Death Penalty Clinic, featured in the Los Angeles Times. In “Whitewashing the Jury Box: How California Perpetuates the Discriminatory Exclusion of Black and Latinx Jurors,” Elisabeth Semel and co-authors examine nearly 700 cases decided by the California Courts of Appeal from 2006 through 2018 involving objections to prosecutors’ peremptory challenges. These challenges allow attorneys to excuse prospective jurors without stating a reason and without the court’s approval. District attorneys used their strikes to remove Black jurors in 72% of these cases, Latinx jurors in 28% of cases, Asian-American jurors in 4% of cases, and white jurors in 1% of cases. Prosecutors justified these strikes based on the prospective juror’s demeanor, their relationship with someone who had been involved in the criminal justice system, and their expressions of distrust or perceptions of bias in law enforcement or the justice system.

In the last 30 years, the California Supreme Court has reviewed 142 cases to determine if they violated Batson v. Kentucky’s rejection of intentional race-based jury selection. They found a Batson violation only three times. Between 2006 and 2018, the appellate courts found error in just 18 out of 683 decisions. “Batson’s requirement that the objecting party prove intentional discrimination allows these biases to operate unchecked,” write the report authors. Rather than the California Supreme Court’s approach to form a “work group” to consider these issues, the authors recommend that the state legislature pursue a “drastic course correction” encompassing significant changes to the state’s Batson procedure.

The study’s main findings are as follows [annotations omitted]:

Many decades after Wheeler and Batson were decided, California prosecutors’ use of peremptory challenges to exclude African Americans and Latinx citizens from juries is still pervasive.

Historically and still today, in California, the overwhelming number of Batson objections are brought by defense attorneys against prosecutors’ peremptory challenges.

Empirical evidence overwhelmingly shows that implicit biases play a significant role in prosecutors’ peremptory challenges. Strikes based on these biases most often adversely affect Black defendants and Black jurors. Implicit biases are, by definition, deeply held and reflexive. Inasmuch as each of us acts on them without awareness, lawyers most often will not recognize their biases, much less be able to acknowledge them. Judges are no better at identifying them. Batson’s requirement that the objecting party prove intentional discrimination allows these biases to operate unchecked.

Our empirical analysis of California appellate court opinions shows that prosecutors routinely and successfully cite a Black or Latinx prospective juror’s distrust of law en- forcement or the criminal legal system to justify a peremptory strike against the juror. Social science research demonstrates that most African Americans and Whites do not share the same views of law enforcement or the criminal legal system. The differences in attitude are long-standing and rooted in the nation’s history of institutional racism, as well as the present-day differential treatment of Blacks and Latinx people by actors in the criminal legal system, including by members of law enforcement. More than 40 years ago, in Wheeler, the California Supreme Court announced that these differences do not support the exercise of peremptory challenges: “The representation on juries of these differences in juror attitudes is precisely what the representative cross-section standard . . . is designed to foster.” California courts long ago lost sight of this goal.

District attorney training manuals on peremptory challenges encourage discriminatory strikes in at least three respects:

*Prosecutors are trained to identify the “ideal juror” as a person who most resembles them—“attached to the community, educated, stable, [and] professional.” They are likewise advised to avoid individuals who are members of groups in which people of color are overrepresented, that is, “less educated people and blue collar workers,” and those who are “unemployed or underemployed” or who have family members experiencing similar economic hardship

*Prosecutors are instructed to strike jurors based on their “gut reactions” to jurors’ facial expressions, body language, clothing, and hairstyle, and to rely on lengthy stock lists of court-approved “race-neutral” reasons to explain their challenges. Social science has repeatedly shown that “gut reactions” are often the product of implicit biases that correlate with racial and ethnic stereotypes.

*Prosecutors are trained to strike prospective jurors who have had or whose relatives have had a negative experience with law enforcement or are distrustful of the criminal legal system. They are, in other words, instructed to exploit the historic and present- day differential treatment of Whites and people of color, especially African Americans and Latinx people, by the police, prosecutors, and the courts.

The California Supreme Court’s definition of a “race-neutral” reason is so expansive that any explanation short of the admission of a discriminatory motive will suffice at Batson’s second step, and, ultimately, defeat a Batson challenge. This also allows prosecutors to rely successfully on a laundry list of judicially approved “race-neutral” reasons when they explain their peremptory challenges. Courts have consistently upheld reasons such as a juror’s prior arrest, a juror’s loved one’s incarceration, or a juror’s distrust of the criminal legal system as facially race-neutral and, overwhelmingly, sufficient to defeat a Batson objection.

We evaluated nearly 700 cases decided by the California Courts of Appeal from 2006 through 2018, which involved objections to prosecutors’ peremptory challenges. In near- ly 72% of these cases, district attorneys used their strikes to remove Black jurors. They struck Latinx jurors in about 28% of the cases, Asian-American jurors in less than 3.5% of the cases, and White jurors in only 0.5% of the cases.

Prosecutors most often gave demeanor-based justifications for their strikes. The next most common reason related to a prospective juror’s relationship with someone who had been involved in the criminal legal system. This was followed almost as frequently by a prospective juror expressing a distrust of law enforcement or the criminal legal system or a belief that law enforcement or the criminal legal system is racially- and/or class-biased.

Prosecutors in these cases successfully used their peremptory challenges against African Americans because they had dreadlocks, were slouching, wore a short skirt and “blinged out” sandals, visited family members who were incarcerated, had negative experiences with law enforcement (often many years before they were called for jury duty), or lived in East Oakland, Los Angeles County’s Compton, or San Francisco’s Tenderloin.

Prosecutors also successfully struck Latinx prospective jurors for frowning, seeming confused, wearing large earrings, stating that a loved one had been wrongfully accused of a crime, expressing a belief that the criminal legal system treats people differently based on their race, or being “kicked off a ladder by a border patrol officer who was chasing” undocumented people three decades earlier.

Between 2003 and 2019, the United States Supreme Court issued a series of decisions that signaled the need for lower courts to more rigorously enforce Batson. The California Supreme Court has largely disregarded those directives. Here are three examples:

For years, at step one of the process, the California Supreme Court required the objecting party to show that it was more likely than not that the strike was based on intentional discrimination. Unless the standard was satisfied, the striking party did not have to give reasons for the peremptory challenge. In 2005, in Johnson v. California, the United States Supreme Court rejected California’s test as unduly burdensome and inconsistent with Batson’s rule that step one is a low threshold; the objecting party need only raise an inference of discrimination. Despite the United States Supreme Court’s intervention, in the 42 step-one cases the state supreme court has since decided, the court has not once found Batson error.

The United States Supreme Court has left no doubt that Batson requires the attorney to provide the reasons for the strikes, and that the trial judge and reviewing courts must base their rulings on the reasons the attorney offers. However, the California Supreme Court has consistently approved speculation by trial and appellate courts about reasons the prosecution could have (but did not) offer for its strikes in order to uphold the denial of a Batson objection.

Since 2003, the United States Supreme Court has endorsed a method of analyzing

a Batson objection known as “comparative juror analysis,” an approach central to each of its subsequent favorable Batson decisions. In over 30 years, the California Supreme Court has never used this analysis to expose discrimination. Rather, in case after case, the state supreme court has declined to engage in comparative analysis, restricted its application, or conducted the analysis but found it unpersuasive. The court’s resistance to this powerful analytic tool also explains its extraordinarily high affirmance rate.

California courts—the California Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal—have an abysmal record in Batson cases. In the last 30 years, the California Supreme Court has reviewed 142 cases involving Batson claims and found a Batson violation only three times (2.1%).

It has been more than 30 years since the California Supreme Court found a Batson violation involving the peremptory challenge of an African-American prospective juror.

It has been more than 30 years since the California Supreme Court found that a trial court committed error in denying a defendant’s objection to the prosecutor’s use of peremptory challenges at the first step of the Batson procedure.

California Courts of Appeal, which follow the state supreme court’s precedent, rarely find error when trial courts deny defense attorneys’ Batson motions challenging the removal of Black and Latinx jurors. From 2006 through 2018, our appellate courts found error in just 18 out of 683 decisions (2.6%).

In our examination of California state cases between 1993 and 2019, which were later reviewed by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in habeas corpus proceedings, the Ninth Circuit granted Batson relief 15% of the time—almost six times more often than the California Courts of Appeal and over seven times more frequently than the California Supreme Court. This is particularly noteworthy because the Ninth Circuit, applying federal law, is obliged to use a much stricter standard of review than that employed by our state courts.

In two opinions in 2019, California Supreme Court and Court of Appeal justices urged immediate, decisive action to remedy Batson’s failure in California. In the words of Su- preme Court Justice Goodwin Liu, it is “past time for course correction.” Justice Liu has repeatedly dissented from the majority in Batson cases since joining the court in 2011. He has criticized the court’s persistent failure to apply Batson’s precedents with the “vigi- lance required by the constitutional guarantee of equal protection of the law.” Justice Jim Humes, a member of the California Court of Appeal, similarly urged that “the time has come” for the state “to consider meaningful measures to reduce actual and perceived bias in jury selection.” In May 2020, in another dissenting opinion, Justice Liu declared that the “Batson framework, as applied by this court, must be rethought in order to fulfill the constitutional mandate of eliminating racial discrimination in jury selection.”

Across the country, members of the state and federal bench—including United States Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer—legal scholars, and some state supreme courts have acknowledged Batson’s failure as a mechanism for eliminating discriminatory peremptory challenges, and have called for or implemented reform. In 2018, the Washington Supreme Court took a leadership role when the court adopted General Rule 37 to reform Batson.

We acknowledge the California Supreme Court’s interest in studying Batson’s shortcomings by announcing the formation of a “work group” in January. There has been no sub- sequent statement regarding the goals of the work group or its membership. Over the last three decades, the court has declined many opportunities to remedy these inequities. The legislature—through the passage of AB 3070—is better suited to effectively address persistent discrimination in jury selection in a timely manner. As this report makes ev- ident, the topics identified for study by the “work group” have been amply studied. The questions posed have been answered. The time for a decisive “course correction” by the California Legislature is now.

![Trial By an Unlawfully Created State Body [a jury]. There are only a few ways that Americans can meaningfully exercise their citizenship; enlisting in the military, running for national office, voting and serving on a jury. Like voting, jury service…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5a5430b290bade59404c2423/1594542430187-Y41LTHMF66ABFHQ1TBXS/Berk+study+1.jpg)