Medical Examiner Ruled Bickings’ Death Accidental but White Cops Just Watched the Black Man Drown. $3M Suit Filed Against Tempe, but Cops Have No Duty to Protect Anyone per 'the Public Duty Doctrine'

/From [HERE] The family of a Black man who jumped into a lake and drowned to avoid answering questions from police plans to file a $3 million wrongful death lawsuit against the city.

The notice of claim, which was filed on Dec. 8, accused the Tempe Fire Department (TFD), the City of Tempe, the Tempe Police Department (TPD), and Tempe Town Lake of negligence that the family said resulted in the May 28 death of 34-year-old Sean Bickings, KNXV reported.

A report for the medical examiner’s office ruled Bickings’ death was an accidental drowning, with methamphetamine intoxication listed as a contributory cause, according to KSAZ.

According to the Tempe city government, police responded to a reported disturbance involving Sean Bickings, 34, and his wife. According to police, when they arrived, they spoke to Bickings and his companion, who cooperated fully and denied that any physical argument had taken place. Neither were being detained for any offense.

While police ran the couple’s names through a database to check for outstanding warrants, for some reason Bickings “decided to slowly climb over a 4-foot metal fence and enter the water” in Tempe Town Lake, according to a statement from the city. Police informed him that swimming wasn’t allowed in the lake — but Bickings wasn’t swimming — he was drowning.

As Bickings begged for help, he drifted away as police watched from safety. He would eventually go under and never resurface. Tempe Fire’s Dive and Rescue team would later find his body.

City Manager Andrew Ching and Police Chief Jeff Glover referred to Bickings’ death as a tragedy in the city’s statement. But it was more than that. It was a fatal reminder that police have no legal duty to protect life.

As FOX29 reports, in a transcript of conversations released by Tempe Police, an officer, only identified as ‘Officer 1,’ was noted as telling Bickings that he won’t be going into the lake.

“I’m drowning,” Bickings, noted as ‘victim’ in the transcript, said.

“Come back over to the pylon,” an officer, noted as ‘Officer 2′ in the transcript, said.

“I can’t. I can’t (inaudible),” said Bickings.

“OK, I’m not jumping in after you,” said Officer 1.

Instead of jumping in after Bickings, the officer threatened to detain his wife for being frantic.

“If you don’t calm down, I’m going to put you in my car,” the officer stated.

“I’m just distraught because he’s drowning right in front of him and you won’t help,” she said.

For several more minutes, Bickings’ wife begged the officers for help until he finally stayed under, never resurfacing.

According to the city’s statement, Tempe has asked the Department of Public Safety (DPS) and Scottsdale Police to examine the Tempe Police response to the drowning.

The three Tempe police officers who responded to the call and witnessed the drowning have been placed on non-disciplinary paid administrative leave pending the investigations, as is customary in critical incidents.

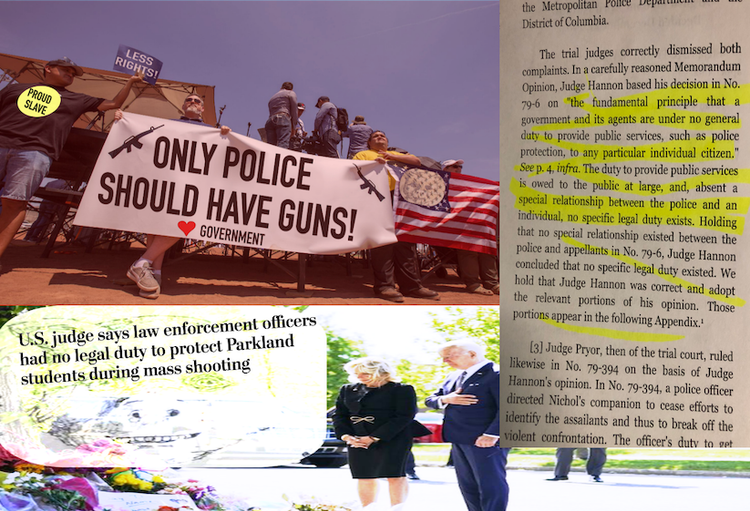

According to the Supreme Court police have no legal duty to protected any victim from violence by other private parties unless the victim was in police custody. [MORE] and [MORE] This means that police cannot be sued for any federal constitutional claim for a failure to protect citizens. Unless a state negligence law exists allowing such a lawsuit, victims cannot hold police liable for a failure to protect from harm from private parties.

The only legal question for victims such as the ones in Ulvalde is whether the students were in the “custody” of the government during the “massacre.” In other mass shootings such as Parkland where a failure to protect children was claimed, the court ruled that students were not in “custody” and dismissed all claims against the police for a failure to protect students. Other victims such as the alleged victims in the Buffalo Supermarket were not in custody and therefore they would have no claims for a failure to protect. Said legal precedent applies regardless of circumstances such as whether police were present or aware of dangers - the Supreme Court has held that police have no legal duty to protect.

The case of Warren v. District of Columbia, 444 A.2d 1 (1981), in which police were present and should have been aware of danger to the victims, clearly articulates the public duty doctrine. The facts were as follows:

In the early morning hours of March 16, 1975, appellants Carolyn Warren, Joan Taliaferro, and Miriam Douglas were asleep in their rooming house at 1112 Lamont Street, N.W. Warren and Taliaferro shared a room on the third floor of the house; Douglas shared a room on the second floor with her four-year-old daughter. The women were awakened by the sound of the back door being broken down by two men later identified as Marvin Kent and James Morse. The men entered Douglas' second floor room, where Kent forced Douglas to sodomize him and Morse raped her. Warren and Taliaferro heard Douglas' screams from the floor below. Warren telephoned the police, told the officer on duty that the house was being burglarized, and requested immediate assistance. The department employee told her to remain quiet and assured her that police assistance would be dispatched promptly. Warren's call was received at Metropolitan Police Department Headquarters at 6:23 a. m., and was recorded as a burglary in progress. At 6:26 a. m., a call was dispatched to officers on the street as a "Code 2" assignment, although calls of a crime in progress should be given priority and designated as "Code 1." Four police cruisers responded to the broadcast; three to the Lamont Street address and one to another address to investigate a possible suspect.

Meanwhile, Warren and Taliaferro crawled from their window onto an adjoining roof and waited for the police to arrive. While there, they saw one policeman drive through the alley behind their house and proceed to the front of the residence without stopping, leaning out the window, or getting out of the car to check the back entrance of the house. A second officer apparently knocked on the door in front of the residence, but left when he received no answer. The three officers departed the scene at 6:33 a. m., five minutes after they arrived.

Warren and Taliaferro crawled back inside their room. They again heard Douglas' continuing screams; again called the police; told the officer that the intruders had entered the home, and requested immediate assistance. Once again, a police officer assured them that help was on the way. This second call was received at 6:42 a. m. and recorded merely as "investigate the trouble" — it was never dispatched to any police officers.

Believing the police might be in the house, Warren and Taliaferro called down to Douglas, thereby alerting Kent to their presence. Kent and Morse then forced all three women, at knifepoint, to accompany them to Kent's apartment. For the next fourteen hours the women were held captive, raped, robbed, beaten, forced to commit sexual acts upon each other, and made to submit to the sexual demands of Kent and Morse.

Denying all claims of liability against the government and the police for a failure to protect the victims the court explained,

“the District of Columbia appears to follow the well established rule that official police personnel and the government employing them are not generally liable to victims of criminal acts for failure to provide adequate police protection.

This uniformly accepted rule rests upon the fundamental principle that a government and its agents are under no general duty to provide public services, such as police protection, to any particular individual citizen.

A publicly maintained police force constitutes a basic governmental service provided to benefit the community at large by promoting public peace, safety and good order. The extent and quality of police protection afforded to the community necessarily depends upon the availability of public resources and upon legislative or administrative determinations concerning allocation of those resources. Riss v. City of New York, supra. The public, through its representative officials, recruits, trains, maintains and disciplines its police force and determines the manner in which personnel are deployed. At any given time, publicly furnished police protection may accrue to the personal benefit of individual citizens, but at all times the needs and interests of the community at large predominate. Private resources and needs have little direct effect upon the nature of police services provided to the public. Accordingly, courts have without exception concluded that when a municipality or other governmental entity undertakes to furnish police services, it assumes a duty only to the public at large and not to individual members of the community.”

The Supreme Court has also ruled that police are not liable under the Due Process clause for a failure to protect even where the police are have adopted a department policy of non-action. In Castle Rock v. Gonzales, 545 U.S. 748 (2005), the Court explained that police have broad discretion to arrest people whenever they want to; even when a court’s restraining order has explicitly ordered the arrest of a violator (as it did in that case) the police have discretion as to whether they will or not arrest.