"We are fighting the police, we’re fighting the media:" Attorney Says DC Cop Shot Kevin-Hargraves Shird in the Head from Behind as He Fled and Posed No Threat to Cop. Lawsuit Pending

/From [HERE] and [HERE] The family of Kevin-Hargraves Shird plans to sue the D.C. police sergeant who shot and killed the 31-year-old man in Fort Slocum Park last July. This comes after the U.S. Attorney’s Office for D.C. announced last week they were declining to file charges.

“While this officer may not ever face criminal charges for what he did, he will have his day in court with the estate of Kevin Hargraves-Shird,” Yaida Ford, a civil rights attorney representing Hargraves-Shird’s family, told DCist/WAMU on Tuesday.

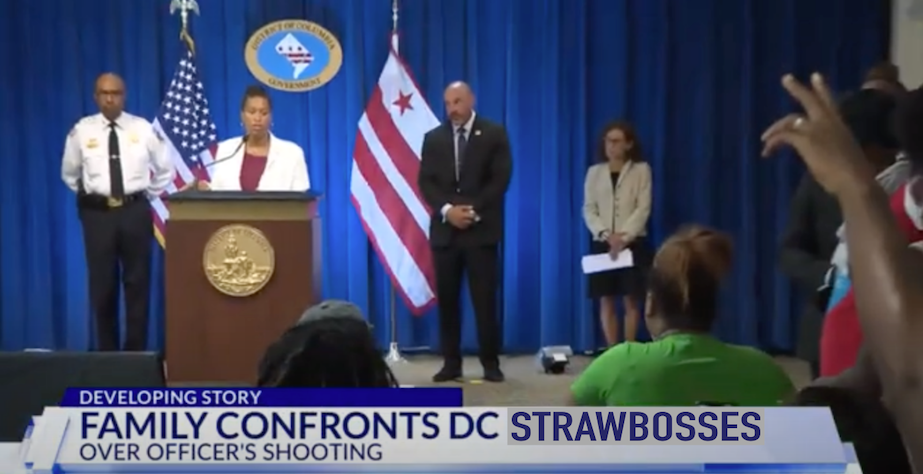

Ford held a press conference on Tuesday afternoon to dispute the assertions made by the office of the U.S. Attorney for D.C in its decision to not prosecute the officer who shot Hargraves-Shird, Sergeant Reinaldo Otero-Camacho. Ford, who met with the USAO last week shortly before their decision was released, said the statement released by the USAO contained “glaring inaccuracies” regarding the evidence in the case. The USAO declined to comment further on the case, and extended “sincerest condolences to the family as they try to process this profound loss,” according to a statement shared with DCist/WAMU on Wednesday morning.

“Both I and the family were really shocked to see some of the remarks,” Ford said. “This statement was very, very concerning and…wildly, wildly irresponsible. For [his family] this ropened a wound. As much as I can try to manage expectations about what’s going to happen with a criminal investigation before a civil case is filed, you cannot prepare them…it was so raw.”

Representing the family, Ford said she will be filing suit against Reinaldo Otero-Camacho in “short order,” alleging the officer did not follow basic D.C. police protocol when he fired his gun without a verbal warning or command.

Otero-Camacho shot and killed Hargraves-Shird in the Brightwood Park neighborhood last summer, while responding to a 911 call regarding a shooting of two juveniles near Georgia Avenue and Longfellow Street NW. Otero-Camacho pursued a white sedan believed to be linked to the 911 call, until the sedan crashed into a curb on Madison Street NW, according to the USAO’s statements. Otero-Camacho, while still in his police car, pulled his gun out, according to body-worn camera footage that was released shortly after the shooting.

Three individuals exited the vehicle, including Hargraves-Shird. According to the USAO’s report, Hargraves-Shird appeared to return to the car to “look through it for something,” and began to flee when Otero-Camacho arrived. The officer, exiting his vehicle, screamed “gun, gun, gun, gun,” and fired one shot, striking Hargraves-Shird in the right ear, according to the USAO.

Matthew Graves, the U.S. Attorney for D.C. (who is white), issued a press release last Thursday stating that after a nearly seven month investigation into the shooting, there was “insufficient evidence” to bring federal or local charges against Otero-Camacho. In the USAO’s brief explanation of its determination, issued on Feb. 9, federal investigators claim that “based on the entry wound of the bullet, as well as Sergeant Otero’s and Mr. Hargraves-Shird’s positioning, Mr. Hargraves-Shird was likely facing Sergeant Otero at the time he fired his weapon.”

Ford disputes this statement, describing the USAO’s claim as “irresponsible” conjecture. A forensic pathologist hired for the family reported that Hargraves-Shird’s head was slightly rotated to the right when he was shot, as if he was looking behind him, according to Ford.

“[The USAO’s] testimony completely contradicts the evidence that Kevin was running away (he was 100 feet from the officer when his body fell after being shot) and that Kevin was looking back over his right shoulder, while running, as the officer said ‘gun, gun, gun, gun,'” Ford said in a press release on Tuesday. “That is how the bullet entered his right ear. If he were facing the officer, the bullet would have hit him in the face or entered his head from the front.”

According to the USAO, the investigation included a review of physical evidence, body-camera footage, radio and forensic reports, an autopsy, and interviews of police and civilian eyewitness accounts. There was a party happening near the shooting that afternoon, but an inflatable moon bounce blocked civilians’ the view of the incident, according to the USAO. Ford said the evidence presented by USAO also does not confirm that Shird was ever carrying the gun that was recovered a few feet from where he fell to the ground. (According to the USAO, the gun has Hargraves-Shird’s DNA on it.)

In the days after the shooting, D.C. Police Chief Robert Contee said he could not comment on Otero-Camacho’s action, seeing as he had not been interviewed yet, and because body-camera footage does not always show the full scope of a scene, or what an officer may have perceived to be threat. But Ford told DCist/WAMU that during her meeting with the USAO, she learned Otero-Camacho had not provided a statement to prosecutors, and instead asserted his Fifth Amendment right. She also said that prosecutors had not produced further evidence to prove that Otero-Camacho believed he was under threat, or that he had issued any lawful command beyond yelling “gun, gun, gun, gun.”

“As these cases play out in real life, it does not appear that officers can ever be wrong in estimating the level of danger with which they are confronted,” she said, adding that the city needs a mechanism of investigating officers that is not linked to the U.S. Attorney’s Office, which often works closely with the Metropolitan Police Department.

The USAO automatically reviews cases of excessive force to determine if the officer violated federal civil rights law or local D.C. law. This determination is a “heavy burden,” according to the USAO, and prosecutors must typically be able to prove the officers “willfully used more force than was reasonable necessary.” Ford said she and Hargraves-Shird’s family understand the burden of proof in criminal cases, but that the USAO’s lack of evidence in its statement was “shocking.”

“The criminal side is different from the civil side of things, there’s a different standard of proof, and I think the family might have been able to accept that. But to then add remarks and statements to a press release when there’s no evidence to back that up, in fact the evidence is contrary to that, was very shocking” Ford said. “It’s one thing to jury process that your loved one has died at the hands of an officer, it’s another to see the U.S. Attorney’s Office make these remarks regarding evidence that just wasn’t there.”

Only one D.C. officer in recent memory has been convicted, or even charged, for an on-duty murder. Terence Sutton was convicted of second-degree murder in the death of Karon Hylton-Brown in December. Hylton-Brown was killed during a chase by Sutton in October 2020. Hylton-Brown was riding a scooter and collided with a vehicle after turning onto a street; he died in the hospital days after the crash. Sutton and his supervisor, Lieutenant Andrew Zabavsky, were also found guilty of obstruction and conspiracy. (They are awaiting sentencing but are likely to appeal the verdict.)

In 2018, the city reached its largest settlement in a case of a fatal police shooting. Officer Brian Trainer shot killed an unarmed Black man, Terrence Sterling, in 2016, and did not not face charges.Years later, the city settled a $3.5 million wrongful death lawsuit with Sterling’s family. (After an internal review, D.C. police concluded that Trainer was not in danger when he fired, and ruled the shooting unjustified.)

Ford conceded that money won’t bring justice for the family — but in the absence of a criminal case, its the only place to turn. Otero-Camacho may still face disciplinary consequences from MPD, as its internal investigation into the shooting is on-going. As of last Friday, a spokesperson told DCist/WAMU that he was currently on a non-contact status, meaning he is not patrolling or engaging with the public.

“I don’t care how much money you give them, they have to accept that the officer or the department or the culture won’t be corrected, and that there will be no genuine accountability,” Ford said.