From [HERE] The Sunday sun was an hour or so from rising over the lake as the Jeffery Pub was closing on Aug. 14, sending patrons out the door and on their way.

It had already been a rowdy end to the night. Just after 4:30 a.m., somebody had called police to report an assault. During the wait for officers to arrive, an altercation spilled out onto the street. And then somebody made a chilling threat.

“I got something for you,” a man allegedly said, adding an obscenity, before he turned and walked a half-block north on Jeffery Boulevard, got into a car and pulled into traffic.

The man, according to court records, then floored the gas pedal and rammed it into the crowd. Four people were struck, including three who died.

The crash occurred at 4:58 a.m., according to court records. That was 27 minutes after the first 911 call about the earlier assault, but no officers had shown up by then.

An officer wasn’t dispatched to the bar until 5:20 a.m. and didn’t arrive until 5:35 a.m., city data shows. That was well after firefighters had arrived to start tending to the wounded — and 64 minutes after the first 911 call.

That lag highlights a staggering reality for Chicago residents: If you dial 911, it may be a while before police show up — even if the situation is so serious that department policy calls for an “immediate” response.

While police do respond relatively quickly to many calls, a Tribune analysis of 2022 city data found that tens of thousands of serious calls lingered in the 911 system for longer than it typically takes to get a pizza delivered.

Chicago has long struggled with times when there are too many calls for assistance and not enough police to respond, but the latest findings illustrate how significant the problem has become and how the burden isn’t shared evenly.

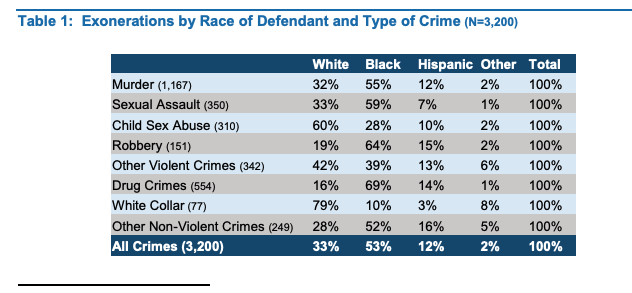

The Tribune’s analysis, based on data the city released last year as required by a legal settlement, also shows the waits for police can be particularly long in several South Side districts where the majority of residents are Black.

In some districts, including District 3 where the Jeffery Pub is located, nearly half the immediate-response calls made from January through November 2022 sat for 10 minutes before operators could dispatch an officer to start heading toward them.

Citywide, the wait for an officer to be dispatched topped an hour for more than 21,000 calls, according to the city’s data. That was roughly 1 of every 24 high-priority calls.

And those delays are only part of the problem. The time it takes to dispatch an officer doesn’t include the time it takes for a 911 operator to ready the call to be dispatched, nor the time it takes once the call is dispatched for the officer to arrive at the scene.

Analyzing the total response time is difficult because for many calls in the city’s data set no arrival time is logged. Even with those limitations, the Tribune identified thousands of additional calls in which officers didn’t report arriving to a scene within an hour of the 911 call being placed.

All told, the wait for police exceeded an hour for more than 29,000 high-priority calls in 2022, the Tribune found, and the true number is likely higher.

Those results are just for the “immediate” dispatch calls, which range from robberies in progress to someone spotted with a gun. Chicago police have two other lower-priority categories for calls — “rapid” dispatch and “routine” dispatch — where the data show that wait times are even more likely to exceed an hour.

A Chicago Police Department spokesperson did not respond to detailed questions about the Tribune’s findings, including possible reasons for delayed responses and why some dispatch times for high-priority calls exceeded 60 minutes. Instead, the department issued a brief statement saying it was “committed to timely response to calls for service within every neighborhood citywide.”

“Patrol resources are frequently analyzed and adjusted to ensure calls for service are responded to by officers in a timely manner,” the statement said.

That vague answer isn’t good enough for the head of the newly seated Community Commission for Public Safety and Accountability, Anthony Driver Jr.

“I think they should prove it,” Driver said. “If that is the case, they should have no problem publicly explaining what these numbers mean and defending the data they are putting on their website.”

The commission, created by city ordinance and formed this summer, was intended to give community leaders more input into who runs the police department and how it operates. The commission quickly became the latest entity to question what Chicago police are doing to better position officers across the city, particularly in an era when the number of active officers has shrunk.

Driver said the Tribune’s findings reinforce the dramatically different realities Chicagoans experience depending on where they live.

“It doesn’t instill confidence ... that when I call the police, as a Black man on the South Side, that I will get the same response as some of our North Side counterparts,” he said.

Missing data, chronic delays

Last year, the city quietly began posting charts on police response times, based on the same data it was forced to release as part of the legal settlement reached in fall 2021.

Inexplicably, the charts focused only on the final portion of a response: the time it takes, once officers are dispatched to a scene, for the first officer to arrive. In essence, the charts measure the travel time for officers, excluding the time it took for a 911 operator to pick up the phone, to discern the nature of the call and to hand the call off to a dispatcher, as well as the time that elapsed before the dispatcher directed an officer to the scene.

The charts also come with a big caveat: The data they’re based on doesn’t include all high-priority calls. In a third of those calls, the department didn’t track when officers arrived at the scene, so those calls were excluded from the department’s calculations. The department also warned that some of the arrival times logged may be inaccurate.

The city has said officers racing to high-priority calls may be too distracted in life-or-death situations to log arrival times properly. But the Tribune found record keeping was even spottier for lower-priority calls, such as parking violations, which suggests that adrenaline rushes aren’t always to blame.

Even given these limitations, the data on officers’ travel times isn’t flattering to the department.

In November, officers’ median travel time to the scene was 9.5 minutes for the highest-priority calls. In New York City, by contrast, the equivalent figure was less than 4 minutes, according to numbers posted online for a similar period. (In cases where an event results in multiple 911 calls, the earliest dispatch and arrival times are used to measure responses.)

Within Chicago, the data shows travel times varied dramatically among the city’s 22 police districts, ranging from a median of 5.8 minutes to nearly 12 minutes. (A median means half the calls took more time and half took less.)

But perhaps the most troubling revelations come from data that’s missing from the posted charts: the time it takes to send out an officer after the 911 operator readies a call for dispatch.

In essence, that’s the middle leg of the emergency response, the one before the travel leg that the city charted online. This information was buried in massive data sets the city posted at the bottom of the website, below the charts. Unlike the travel leg, times are listed for nearly every call, and reporters analyzed those numbers for all calls received from January through November 2022.

There will always be some lag when dispatching police, but it should be minimal. In New York City, for example, for its highest-priority calls during a similar period, that city reported a median time of 90 seconds between the time a 911 operator transferred the call to a dispatcher and the time when the first officer started heading toward the scene.

In Chicago, the Tribune found the same measurement for high-priority calls was more than double New York City’s, with a median time of 3.1 minutes. And in some places, the lag can be far greater, particularly in some South Side districts. [MORE]