Black Man Serving Life Sentence Released from Prison - Confession Induced by Chicago Police Torture

/

From [HERE] CHICAGO – As a former Chicago police commander reported to federal prison Wednesday for lying about the torture of murder suspects decades ago, a man his detectives allegedly beat into confessing learned he was being freed after spending 25 years in prison.

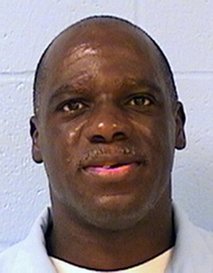

Jon Burge, whose name in Chicago is synonymous with police brutality and racism, turned himself in Wednesday morning to begin a 4 1/2-year sentence at Butner Federal Correctional Complex in North Carolina. Hours later in Chicago, a judge ordered 45-year-old Eric Caine released from Menard Correctional Center after prosecutors conceded that they didn't have enough evidence to convict Caine of murder again without the suspect confession he gave police in 1986.

"On the day that Jon Burge is headed for prison, Eric Caine got word he is coming home," said Caine's attorney, Russell Ainsworth.

Caine was serving a life sentence after being convicted with another man in the 1986 stabbing a couple on Chicago's South Side. Caine was convicted largely on the basis of his confession and statements made during police questioning by his co-defendant, Aaron Patterson, who also alleged his confession was coerced and who was sentenced to death.

Both men claim Burge's "Midnight Crew" of detectives tortured them into confessing. After allegations surfaced that the white commander and his detectives were coercing black suspects into confessing to crimes, prosecutors began reviewing past convictions involving Burge's squad. Just before leaving office in 2003, Gov. George Ryan, who had put a moratorium on capital punishment after several condemned inmates were exonerated, cleared Death Row and pardoned four condemned inmates, including Patterson.

Ryan did not pardon Caine, though, and Ainsworth speculates that the former governor may have only freed Patterson because he was on Death Row and Caine wasn't and Ryan may not have known about Caine's case.

Patterson "got the attention, the publicity and the pardon and Eric Caine was left behind," Ainsworth said.

Wednesday's developments highlight the plight of about 20 men still behind bars whose cases, unlike Caine's, aren't up for review and whose hopes of getting their convictions overturned currently rest with a commission set up two years ago to investigate claims of police torture. Thus far, the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission has yet to look at a single case and doesn't plan to for months.

"It's just incredibly frustrating," said Rob Warden, director of the Northwestern University School Center on Wrongful Convictions and a member of the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission that was formed in response to the allegations surrounding Jon Burge and detectives under his command.

For men like Leonard Kidd — who contends he confessed in 1984 to a quadruple homicide after Burge's men applied electric shocks to his genitals and tortured him in other ways — the commission may be the last chance to get the justice system to consider claims that Burge and his men shocked, beat and suffocated them into confessions.

"What we want is for Leonard Kidd to have a trial without the admission of a coerced confession," said Tiffany Boye Green, who represents Kidd. Kidd also has a separate claim in connection with a conviction for setting a fire that killed 10 children.

Another claimant, Derrick King, says officers beat him with a baseball bat and a telephone book in 1980 to force him to confess to a shooting death at a candy store.

But before their claims can be considered, Kidd, King and others must endure the bureaucratic red tape that comes with the creation of a new state commission.

Between all the state requirements including publishing the commission's rules and regulations for a total of 90 days, it will be "four months before we can say, 'OK, we've got the people in place, the rules and regulations in place,'" said Patricia Brown Holmes, the former judge who chairs the commission.

The commission has the authority to subpoena witnesses, but it can only recommend that the Cook County Circuit Court's chief judge order an evidentiary hearing — a recommendation the judge is free to ignore. Attorneys who have handled torture cases worry that its limited power might lead to a repeat of what happened in 2006 when a special prosecutor concluded that Burge and his men tortured suspects into confessions but said nothing could be done because the statute of limitations had long since passed.

"There is a chance for some very righteous pontificating with no real substance behind it," said Locke Bowman, who has represented several men who accuse Burge of torture.

Bowman and attorney G. Flint Taylor, who has also handled several torture cases, said the commission should simply recommend and a judge should order new evidentiary hearings for all those who claim their convictions were at least in part the result of confessions elicited by Burge or his men.

Brown disagrees, saying the commission should examine each case and refer them to the judiciary on their individual merits — or run the risk of the commissions' recommendations not being taken seriously.

"If they take a hard look at each case and not just start tossing stuff at (judges), then the chief judge is not going to just take a look and toss them in a drawer," she said.

Warden said enough evidence of torture has surfaced — including at Burge's own trial — that there is no need for a case-by-case review. "Everybody gets an evidentiary hearing," he said. "Period. Boom."

He said the commission could determine in a matter of hours whether at least some of the cases deserve new hearings.

"If there is a timely allegation of torture and a confession extracted by a known member of the Burge crew that was admitted at trial, then that person should get an evidentiary hearing," Warden said.

Warden wonders, though, whether anything the commission does will actually mean any jail doors will swing open for those tortured in confession.

"Unfortunately, the fact is, it's possible to torture a guilty person," he said. "Burge showed that when he tortured (convicted police killer) Andrew Wilson."

Warden said nobody would want to be blamed for putting killers back on the street.

At the same time, Ainsworth said that perhaps Caine's case will help those inmates who, like Caine, are behind bars in large part if not entirely because of coerced confessions.

"It is our hope that through Eric Caine's case we can help shed some light on the plight of those persons who are just as innocent as those persons who have been exonerated by DNA but don't have that DNA evidence to point to," he said.