NYPD Commissioner to Give Gun Back to Officer who Killed Diallo: Unarmed Black Man Shot 41 Times by NYPD

/ From [HERE] More than 13 years after the police shooting of Amadou Diallo, Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly has agreed to restore a service weapon to one of the four New York City officers involved, a decision that Mr. Diallo’s mother characterized as a betrayal.

From [HERE] More than 13 years after the police shooting of Amadou Diallo, Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly has agreed to restore a service weapon to one of the four New York City officers involved, a decision that Mr. Diallo’s mother characterized as a betrayal.

Mr. Kelly had indicated “that he was not going to give back the gun,” Kadiatou Diallo said in a phone interview from her home in Maryland. “Now he has turned around and given back the gun. We want to know why. Why did he change his mind?”

The police fired 41 shots, killing Mr. Diallo as he stood in the vestibule of his apartment building in the Bronx on Feb. 4, 1999. Although the officers said they believed he had a gun, Mr. Diallo was unarmed.

The Police Department offered no official explanation on Tuesday about restoring a gun to the officer, Kenneth Boss. But a law enforcement official familiar with Mr. Kelly’s reasoning pointed to the recent exoneration of another officer, Michael Carey, who fired 3 of 50 bullets shot at Sean Bell, who was killed on the morning of his wedding outside a Queens nightclub in 2006.

“The subsequent exoneration in the trial room of Officer Carey in the Sean Bell case, whose gun-carrying privileges were restored under similar circumstances as the Diallo shooting played a significant role in the decision,” the law enforcement official said.

Officer Carey, who is on full patrol duty in Midtown South, began carrying a firearm in late June.

Patrick J. Lynch, president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, said he believed that Mr. Kelly’s decision, reported Tuesday in The New York Post on Tuesday, was “appropriate and long overdue.”

“This police officer was exonerated in a criminal trial and in a thorough departmental review and there was no reason to deny him full restoration,” Mr. Lynch wrote in a statement.

The fusillade of bullets, 19 of which struck Mr. Diallo, prompted furious protests against the police. The officers, all white and members of the elite Street Crime Unit, said they believed Mr. Diallo had a gun. It turned out to be his wallet.

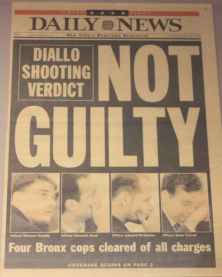

The city convulsed again the next year as a jury acquitted the four officers of all charges. Anguished protesters marched, and relations between the police and many black people soured.

The Police Department later dismantled the street unit, which had come under withering criticism from black leaders, and the city reached a $3 million settlement with Mr. Diallo’s parents, who said profiling by the police had caused their son’s death.

In the years following the verdict, three of the officers opted to leave the force rather than face another painful public battle. Edward McMellon and Richard Murphy have been active duty firefighters for more than a decade, with Mr. McMellon currently in Brooklyn and Mr. Murphy in the Bronx. Sean Carroll retired in 2005 after being reassigned to a police job at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn.

Officer Boss also worked at the field, assigned to modified duty for the Emergency Service Unit’s training school and repair shop. He carried an identification card stamped “No firearm.”

But determined to remain a police officer, he pressed ahead in court to remove what he saw as an enduring blot on his record.

Filing suit in 2002, he maintained that the Police Department rules allowed him to perform regular police duties, including carrying a weapon. Not having one, he said in court documents, earned him the “mocking moniker ‘Kenny No-Gun’ among his colleagues.”

But a state court found that the police commissioner had the ultimate say over whether an officer could have a gun or not, a decision that was upheld on appeal. Commissioner Kelly said in court documents that if Officer Boss were to carry a weapon again, then he and the department could face “prejudgment” should he fire it.

In 2006, Officer Boss took military leave and served as a Marine in Iraq. When he returned with an achievement medal for combat operations, Officer Boss again asked to get his gun back. Again he was denied.

He then sued in court, only to see that case dismissed as well.

Edward W. Hayes, the lawyer who represented Officer Boss, described his client as a “cop’s cop.”

“He loves the Police Department,” Mr. Hayes added. “This is a guy who loves being a policeman. Loves it. And he loves helping people.”

Mr. Hayes said he never gave up on Officer Boss throughout his long legal battle. “I would have represented this guy till he was 100,” he said.

Officer Boss is now assigned full duty to the Special Operations Division, which responds to critical and emergency situations, like water rescues and hostage negotiations. “There are not many cops who have his record in the Marine Corps, so you want to save him for the really bad problems,” Mr. Hayes said.

Yet Ms. Diallo said Officer Boss’s determination to get his gun back had forced her to relive her son’s death repeatedly.

“For Kenneth Boss to be stubborn and continue challenging this, it’s like he’s killing my son all over again,” she said. “He is opening up the wound.”

In many ways, Ms. Diallo has become the public face of tragic fatal police shootings. She traveled from her Maryland home to Manhattan on Friday to console the mother of Mohamed Bah. The police shot and killed Mr. Bah, 28, in the doorway of his Harlem apartment when, according to the police, he lunged at officers with a knife on Sept. 25. Mr. Bah’s mother called 911 for help after her son locked himself in his apartment with a knife.

Ms. Bah and Ms. Diallo have been friends for years. They had lived near each other in Liberia and the two families socialized, according to Ms. Diallo, who added that the timing of Mr. Kelly’s decision, on the heels of Mr. Bah’s death, added a new layer of grief.

Ms. Diallo said her three grandsons, 7-year-old triplets, one named Amadou, look at her son’s photograph on her living room wall and ask her what happened to their uncle. He is smiling in the photo, frozen at age 22.

“We never discuss this tragedy with them,” Ms. Diallo said. “They look at the picture and say: ‘Grandma, can you tell us what happened to our uncle? Was it a car accident? Was he sick?’ I tell them, ‘One day I will tell you.’ ”