4th Amendment for Whites Only? Michigan State Troopers Use Flint Sidewalk Law to Stop & Frisk Black Men

/

Don't Blame the Sidewalk Law. The operating system (OS) of White supremacy is the cause and effect of white people's genocidal conduct towards non-whites - not stop & frisk laws, stand your ground self defense laws or here, sidewalk ordinances in Flint used by State Troppers to stop Black men. It is the application of such laws by racist citizens, police, prosecutors, jurors and judges that creates injustice for non-whites.

Neely Fuller explains that a "non-law" is any law that is used in such a manner as to promote injustice. It is deception or delusional to believe that the elimination of such laws will have an affect on the way in which white people (including law enforcement) relate to non-whites. [MORE] and [MORE] If you don't understand the context of white supremacy/racism you will only be confused by these issues.

From [HERE] Non-white people walking in the street instead of using available sidewalks in residential Flint neighborhoods are being stopped -- and in at least some cases searched -- by state police, sparking complaints from some defense attorneys who claim it amounts to racial profiling.

Fenton-based attorney Steven Shelton dubbed the practice "walking while black" and is one of four attorneys arguing that the stops are not justified, although no formal complaints have been lodged against the practice.

In at least three recent court cases, black men have been stopped while walking in the roadway in northside neighborhoods and subsequently arrested because police allegedly found the men in possession of guns or drugs.

Shelton claims troopers have no legal authority to stop and search people because they are walking in a residential street, even if there is a sidewalk -- an argument that one Genesee County Circuit judge agreed with in a ruling.

"If you are young, black and in Flint your constitutional rights are almost worthless," said defense attorney Frank J. Manley, who said he has fielded complaints from residents who were stopped while walking in the street.

While the legitimacy of the stops has been questioned in three court cases, Shelton said there is no way of knowing how many, if any, other residents have been stopped for walking in the street. "We only see the cases where they actually find something," said Shelton.

Michigan State Police Capt. Greg Zarotney, chief of staff for the police agency's director, who is white, said that walking in the street when a sidewalk is available is a violation of law and that the stops are justified. Zarotney specifically cited a state law that prohibits pedestrians from walking on highways in places where sidewalks are provided. He also denied that race has been a factor in any stops. State police policies specifically ban the use of race as a reason to stop and question someone.

"They're out there trying to ensure that all laws are being enforced in these areas," Zarotney said. None of the men were ticketed for the alleged walking in the street violation, which Zarotney said is typical when a more serious violation is discovered (given after the stop).

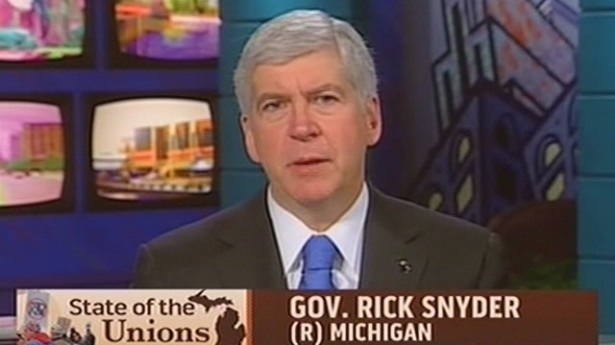

Zarotney said the stops were part of state police directed patrols -- operations that target designated criminal hotspots within Flint. The patrols started in 2001 on a limited basis, but Republican (white party) Gov. Rick Snyder boosted the number of troopers in Flint last year as part of his initiative to fight violent crime in the city.

Billy Chambers was walking on Bonbright Street Aug. 31 when he was stopped by troopers for failing to use the provided sidewalks, according to court records.

When stopped, Chambers told police that he did not have anything illegal on him, according to a federal court affidavit filed by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. The troopers asked if they could pat down Chambers and he agreed, the affidavit says.

Troopers allege they discovered a .38-caliber pistol in Chambers' left-front pants pocket during the search. Troopers said in the affidavit that Chambers told them that he found the gun on the street and kept it hoping to trade it for crack cocaine.

Chambers, who has three previous felony convictions on drug-related charges, was arrested and indicted in Flint U.S. District Court on a single charge of being a felon in possession of a firearm. He pleaded not guilty.

Detroit attorney Richard Korn, who represents Chambers, said he plans to challenge the validity of the arrest. Korn said he visited the site of the arrest and took pictures of the condition of the sidewalks.

"It's treacherous," said Korn, who claims his client was targeted by police because he is black.

Korn said he plans to make it an issue when he files motions in the case in December and will attempt to subpoena state police records on other similar stops in Flint to see if there is a pattern.

Walking with a baggie

Michael Anthony Johnson, 30, was arrested by troopers at about 7 p.m. Aug. 2 as he walked in Lyon Street near Wood Street, according to court records.

A trooper testified during his preliminary exam that police stopped Johnson because he was walking in the street rather than on the provided sidewalks.The trooper also testified that he saw Johnson put a plastic bag containing a white substance into his pocket after troopers got out of the patrol car to talk with him about walking in the street.

When searching Johnson, police allegedly found powdered cocaine, crack cocaine and multiple bags of marijuana.

Johnson was charged with possession of a controlled substance and possession of marijuana.

Although heavy weeds have partially overgrown portions of the sidewalk in that area, Johnson's attorney did not make an issue of the sidewalk's condition in his argument against the stop.

Instead, Shelton argued to Genesee Circuit Judge Archie Hayman that state law did not apply to Flint's residential streets because the law specifically references walking along highways.

A 1911 Michigan Supreme Court case involving a lumber company defined highway as a generic term for all kinds of public thoroughfares, including streets, according to a Supreme Court ruling. But, Shelton argued that the language in the state's vehicle code created a distinction between streets and highways.

Hayman agreed with Shelton, saying that troopers had the right to tell Johnson to get out of the street if they were attempting to drive on it, but said there is no law against walking in the street.

However, the charges against Johnson were not dropped because Hayman also ruled that the troopers had the right to stop Johnson after they witnessed him put the suspected bag of drugs into his pocket as they approached.

Like Korn, Shelton believes the main reason his client was targeted for the stop by police was because he is black.

Johnson pleaded guilty to possession of marijuana and a lesser charge of maintaining a drug house or vehicle. Sentencing is scheduled for Dec. 9.

Cocaine and a bad sidewalk

Draper L. Miles was walking on Albert Street near Witherbee Street at about 4 p.m. July 16 when he was stopped by three Michigan State Police troopers in a fully-marked patrol vehicle, according to a state police report.

Troopers claimed in their report that Miles, 36, of Flint, was walking in the middle of the residential street and was carrying a purple Crown Royal Whisky bag when he was stopped for failing to walk on the provided sidewalks.

The troopers reported that Miles agreed to a search, although Miles' attorney denies he gave consent.

"When asked if he would mind if we looked inside the bag, Miles responded, 'Sure, go ahead,'" the troopers wrote in their report.

Troopers discovered powder cocaine, a crack pipe, miscellaneous pill bottles, a small amount of marijuana and an electronic scale, according to the report.

Miles, who has no previous felony convictions, was arrested and taken to Flint city lockup. He was charged with possession of a controlled substance, a four-year felony.

Miles' attorney, Flint-based Peter Philpott, challenged the arrest, saying in court that Miles was forced to walk in the street due to the poor condition of the sidewalks in the area.

"He was doing nothing illegal, but walking in the street," said Philpott, who unlike Korn and Shelton stopped short of directly calling his client a victim of racial profiling because he said he doesn't have enough evidence yet to establish a pattern of racially motivated stops.

Philpott said the sidewalk on the east side was covered with garbage, debris and vegetation at the time of the stop.

"It was impassable," said Philpott, who took photos and videos showing the condition of the sidewalk.

Prosecutors dropped the charge because troopers did not show up to an Oct. 30 hearing on the legality of the stop -- an absence that state police blame on a miscommunication.

"The troopers' absence at the court hearing appears to be due to a mix-up with the delivery of the subpoena as the troopers involved in the case are currently assigned to the Groveland (Township) detachment and the subpoenas did not get delivered to them at the detachment," Zarotney said. "Our internal processes regarding subpoena delivery have been improved and this type of issue should not occur in the future."

Genesee County Prosecutor David Leyton said he hasn't decided if he will re-file the charge against Miles.

When can police make stops?

Ronald J. Bretz, a [white] professor at Lansing-based Cooley Law School, said police need reasonable suspicion of criminal activity to justify stopping someone.

"Racial profiling isn't legal if it's the only reason for a police stop," said Bretz, a former state appeals public defender who specializes in criminal law.

If a judge decides a stop is the result of racial profiling, Bretz said the judge can keep evidence found during any subsequent search from being used at trial.

Leyton [who is white] said he would not allow evidence collected during a stop he believed to be unconstitutional to be used in by police seeking charges. Leyton said his office has a "healthy adversarial relationship" with the police and serves as the first line of protection when it comes to the constitutional rights of those charged with crimes.

"We take that very seriously," said Leyton.

However, in his nine years as prosecutor, Leyton said he has never seen a case that he believed police used race as the main reason for stopping a suspect.

"If defense counsel believes stops are improper, they can [months later at trial after the stop, detention, search, arrest and paering of the case -BW ], and sometimes do, contest the stop," Leyton said.

What is racial profiling?

The U.S. Department of Justice states that racial profiling rests on the "erroneous assumption" that a particular race or ethnicity is more likely to break the law than other races or ethnicities.

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that racial profiling violates constitutional provisions for equal protection under the law when it is a sole basis for a police stop. Law enforcement can use race when it is a specific factor of a crime, such as searching for a suspect from a specific ethnicity.

The issue of racial profiling has sparked ongoing legal and social debate for decades, with everything from MTV exploring the issue of "Driving While Black" in 1999 and an ACLU report that same year claiming that racial profiling of minority drivers was rampant in the nation.

U.S. Rep. John Conyers Jr., D-Detroit, has introduced federal legislation -- that has been introduced four previous times -- which would ban law enforcement agencies from profiling based on skin color or religious practices four times. The proposals, however, have not been passed into law. The current bill has been referred to a House subcommittee.

The claims of racial profiling in Flint aren't the first to be directed at the Michigan State Police.

State Police Director Col. Kriste Kibbey Etue announced in March 2012 that her agency would conduct an internal review after the ACLU filed a written complaint claiming that a Grand Rapids man and U.S. citizen was detained by a motor-carrier officer and improperly turned over to an immigration official because he was of Mexican descent and did not speak English fluently.

"The department does not condone, support or teach any type of bias profiling, nor do we endorse discriminatory enforcement practices," Etue said at the time. "Any enforcement action that is race-based, consciously or thoughtlessly, is neither legal nor consistent with MSP principles, values or policies, and will not be tolerated by the department."

The National Institute of Justice has argued that law enforcement agencies should avoid racial profiling techniques because the tactics could make their work in the community more challenging by straining the relationships people in the community have with police.

Manley agreed: "These tactics have created a siege mentality against many law-abiding citizens by lumping law-abiding citizens in with criminals."

Flint NAACP President Frances Gilcreast said her group has gotten four to five complaints about questionable police stops this year but said she has not filed a formal complaint with local officials.

Zarotney, of the state police, said his agency has not received any negative feedback from residents regarding the agency's operations in Flint.

He said the Flint post has adopted an open-door policy to address citizens' concerns about their patrols. The post also has hosted town hall meetings for community members to interact with troopers.

Zarotney said that the state police take complaints filed against troopers seriously. Anyone with a complaint should contact the Flint post or reach out to the agency's internal affairs department directly, he said.