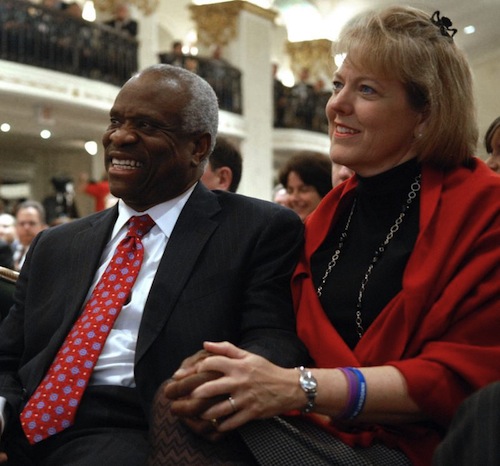

Clarence Thomas has not Spoken a Single Word in Court in Five Years

/From NY Times

His Wife Does all the Talking [MORE]

WASHINGTON — The anniversary will probably be observed in silence.

A week from Tuesday, when the Supreme Court returns from its midwinter break and hears arguments in two criminal cases, it will have been five years since Justice Clarence Thomas has spoken during a court argument.

If he is true to form, Justice Thomas will spend the arguments as he always does: leaning back in his chair, staring at the ceiling, rubbing his eyes, whispering to Justice Stephen G. Breyer, consulting papers and looking a little irritated and a little bored. He will ask no questions.

In the past 40 years, no other justice has gone an entire term, much less five, without speaking at least once during arguments, according to Timothy R. Johnson, a professor of political science at the University of Minnesota. Justice Thomas’s epic silence on the bench is just one part of his enigmatic and contradictory persona. He is guarded in public but gregarious in private. He avoids elite universities but speaks frequently to students at regional and religious schools. In those settings, he rarely dwells on legal topics but is happy to discuss a favorite movie, like “Saving Private Ryan.”

He talks freely about the burdens of the job.

“I tend to be morose sometimes,” he told the winners of a high school essay contest in 2009. “There are some cases that will drive you to your knees.”

Justice Thomas has given various and shifting reasons for declining to participate in oral arguments, the court’s most public ceremony.

He has said, for instance, that he is self-conscious about the way he speaks. In his memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son,” he wrote that he had been teased about the dialect he grew up speaking in rural Georgia. He never asked questions in college or law school, he wrote, and he was intimidated by some fellow students.

Elsewhere, he has said that he is silent out of simple courtesy.

“If I invite you to argue your case, I should at least listen to you,” he told a bar association in Richmond, Va., in 2000.

Justice Thomas has also complained about the difficulty of getting a word in edgewise. The current court is a sort of verbal firing squad, with the justices peppering lawyers with questions almost as soon as they begin their presentations.

In the 20 years that ended in 2008, the justices asked an average of 133 questions per hourlong argument, up from about 100 in the 15 years before that.

“The post-Scalia court, from 1986 onward, has become a much more talkative bench,” Professor Johnson said. Justice Antonin Scalia alone accounted for almost a fifth of the questions in the last 20 years.

Justice Thomas has said he finds the atmosphere in the courtroom distressing. “We look like ‘Family Feud,’ ” he told the bar group.

Justice Thomas does occasionally speak from the bench, when it is his turn to announce a majority opinion. He reads from a prepared text, and his voice is a gruff rumble.

He does not take pains, as some of his colleagues do, to explain the case in conversational terms to the civilians in the courtroom. He relies instead on legal Latin and citations to subparts of statutes and regulations.

His attitude toward oral arguments contrasts sharply with that of his colleagues, who seem to find questioning the lawyers who appear before them a valuable way to sharpen the issues in the case, probe weaknesses, consider consequences, correct misunderstandings and start a conversation among the justices that will continue in their private conferences.

By the time the justices hear arguments, they have read briefs from the parties and their supporters, and most justices say it would be a waste of time to have advocates merely repeat what they have already said in writing.

“If oral argument provides nothing more than the summary of the brief in monologue, it is of very little value to the court,” Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist wrote in 1987.

Lawyers who appear before the court and scholars who study it are of mixed minds about Justice Thomas’s current silence. His views can be idiosyncratic, and some say lawyers deserve a chance to engage him before being surprised by an opinion setting out a novel and sweeping legal theory.

Others say they are just as happy not to waste valuable argument time on distinctive positions unlikely to command a majority in major cases.

Justice Thomas routinely issues sweeping concurrences and dissents addressing topics that had not come up at argument.

He asked no questions, for instance, in a 2007 case about high school students’ First Amendment rights. In a concurrence, he said he would have overturned the key precedent to rule that “the Constitution does not afford students a right to free speech in public schools.”

Neither side had advanced that position. The basis for and implications of his concurrence were not explored at the arguments, because, by asking no questions, Justice Thomas did not tip his hand.

No other justice joined Justice Thomas’s opinion. “If Justice Thomas holds a strong view of the law in a case, he should offer it,” David A. Karp, a veteran journalist and third-year law student, wrote in the Florida Law Review in 2009. “Litigants could then counter it, or try to do so. It is not enough that Justice Thomas merely attend oral argument if he does not participate in argument meaningfully.”

Justice Thomas’s last question from the bench, on Feb. 22, 2006, came in a death penalty case. He was not particularly loquacious before then, but he did speak a total of 11 times earlier in that term and the previous one.

His few questions were typically pithy and pointed. He pressed a defense lawyer, for instance, in a 2005 argument about possible race discrimination in jury selection.

“Is there anything in the record to alert us to the race of the prosecutor?” he asked. “Would it make any difference? There seemed to be some suggestion that there are stereotypes at play.”

Justice Thomas’s most famous comments also came in a case involving race.

In a 2002 argument over a Virginia law banning cross burning, his impassioned reflections changed the tone of the discussion and may well have altered the outcome of the case. He recalled “almost 100 years of lynching” in the South by the Ku Klux Klan and other groups.

“This was a reign of terror, and the cross was a symbol of that reign of terror,” he said. “It was intended to cause fear and to terrorize a population.”

The court ruled that states may make it a crime to burn a cross if the purpose is intimidation.