Maulana Karenga - MLK and Obama in Libya: Tenet or Tactic of Humanitarian Concern

/By Dr. Maulana Karenga. He is a professor of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.MaulanaKarenga.org.

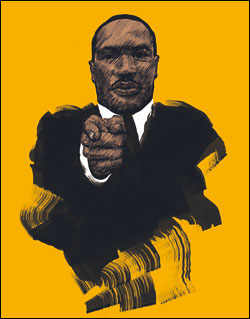

From [HERE] As we commemorate the martyrdom of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (4/4/1968) and reflect on his awesome sacrifice and meaning for us, the country and the world, we must first distance him from the dominant society‟s calculated construction of him as forever fashioned and frozen in an immobilizing dream, drained of his active anger at injustice, his assertive advocacy for the poor and vulnerable, his opposition to war as an enemy of humanity and the poor, his insistence on a peace with justice, and his dedicated resistance to the triple evils of racism, materialism and militarism. Indeed, he noted that, those who raised questions about the width and wisdom of his field of moral vision which includes resistance to war and commitment to the pursuit of peace, “have not really known me, my commitment or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.”

Thus, to honor and rightfully remember King, we must not only have an expansive conception of his life, work and teachings, but also apply this understanding to the context of our time, to the world in which we actually live. Certainly, then, King‟s teachings on the immorality, waste and unwisdom of war is appropriate. What King offers us is a genuine humanitarian concern that is a fundamental tenet of his moral vision, not a tactic of hypocritical and selective humanitarian concern presented by President Obama to justify and mask a war of resource plunder and imperial predation.

In viewing and responding to the U.S. government‟s war of resource robbery against the Libyan people under the tactical guise of humanitarian concern, King‟s teachings on war, especially as delineated in his “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” lecture, is an important focus for understanding and honoring his life and sacrifice, and as he says, a compelling call for us to move beyond apathy, conformity and pathetically mindless patriotism to “the high grounds of firm dissent based upon the mandates of conscience and the reading of history.” For his opposition to the Vietnam War is clearly applicable to this current war against Libya.

In viewing and responding to the U.S. government‟s war of resource robbery against the Libyan people under the tactical guise of humanitarian concern, King‟s teachings on war, especially as delineated in his “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” lecture, is an important focus for understanding and honoring his life and sacrifice, and as he says, a compelling call for us to move beyond apathy, conformity and pathetically mindless patriotism to “the high grounds of firm dissent based upon the mandates of conscience and the reading of history.” For his opposition to the Vietnam War is clearly applicable to this current war against Libya.

King states that his first reason for opposition to the war was recognition of “war as an enemy to the poor,” and that “America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor as long as adventures like Vietnam continue(d) to draw men, skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube.” Even now, we are told we have no money for education, employment, healthcare, housing, rebuilding the infrastructure, reducing poverty, but much to make war— $500 million worth within 10 days of brutal bombing of the Libyan people to help them fight a war they, themselves, did not start, and undetermined secret costs of special operations to build a pretense of a liberation movement and to kill the uncooperative and resistant.

Second, King found it morally unacceptable for Blacks to be sent “to fight and to die in extraordinarily high proportions relative to the rest of the population.” And he criticized the “cruel irony” of Blacks and Whites, unequal and segregated in America, joining in “brutal solidarity” in burning and pillaging the villages of Vietnam. He called this the “cruel manipulation of the poor” which remains a problem for people of color in a volunteer army made up of so many who, joining to improve their lives, end up as victims of unnecessary death, disabling wounds and returning without finding the education, care and support promised and rightfully expected.

Furthermore, Dr. King rejects war as a way to solve problems, reporting how young Black men in revolt in the 60s questioned him for counseling them against violence while America, itself, was “constantly using massive doses of violence to solve its problems, to bring about the changes it wanted.” He says then “I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed . . . without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government.” It was a contradiction of proportion, impact and national hypocrisy he could not allow.

King also was genuinely concerned with the SCLC goal “To save the soul of America,” and argued that “no one who has any concern for the integrity and life of America today can ignore the present war.” Indeed, he maintained that such an unjust and aggressive war, poisons and pollutes the body politic, destroys the moral status and claims of the country, and leads inevitably down the path of ruin. He states that America can never be saved as long as it destroys the lives, lands and hopes of men and women the world over. Thus, to dissent and vigorously oppose such destructive practices is to be “working for the health of our land.”

Furthermore, King states he also has a responsibility, reaffirmed with his receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize, “to work harder than

. . . before for „the brotherhood of man‟.” It is at the same time a composite part of his life commitment to his ministry and his faith, Christianity. In fact, he says, “to me, the relationships of this ministry to the making of peace is so obvious that I sometimes marvel at those who ask me why I‟m speaking against the war.” And given this stress on peace and brotherhood so central to his faith and ministry, he asks of his relations with people defined as “enemies,” “(should) I threaten them with death or must I not share with them my life?”

Finally, Dr. King states that the road that led him from Montgomery and the struggle for civil rights to the struggle for peace and against “the curse of war” is his belief that his Divine Father and faith privilege the “suffering and helpless and outcast” and he is called to speak for them wherever they are, especially in the midst of war. He asserts that this is “the privilege and burden of all of us who deem ourselves bound by allegiances and loyalties broader and deeper than nationalism and which go beyond our nation‟s self-defined goals and positions.”

Indeed, he concludes, “we are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation and for those it calls „enemy,‟ for no documents from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers.” And surely what he said of the Vietnamese counts no less for the Libyan people, an African people, whose country‟s vulnerability and resource value have made them prime candidates for the curse and savage plunder of imperial war.