No Accountability for Intentional Conduct: Biased Supreme Court shields prosecutors in wrongful convictions

/From [HERE] Though new DNA testing has shown hundreds of convicts to be innocent, the court has protected prosecutors from lawsuits and balked at letting prisoners reopen cases.

Reporting from Washington— One innocent man, from Arizona, was sent back to prison for raping a child when the Supreme Court ruled he had no right to evidence that would later set him free.

Another innocent man, from Louisiana, was convicted of murder and came within weeks of being executed because prosecutors had hidden a blood test that later freed him.

The two men were linked at the Supreme Court last week by Justice Antonin Scalia, who argued that criminal defendants have no right to "potentially useful evidence" that "might" show they were innocent.

Since the 1990s, the advent of DNA evidence has swept across the American criminal justice system and revealed that hundreds of convicted prisoners were innocent. Yet, throughout that time, the Supreme Court has shielded prosecutors from claims that they hid evidence that could have revealed the truth and has been reluctant to give prisoners a right to reopen old cases.

Since the 1990s, the advent of DNA evidence has swept across the American criminal justice system and revealed that hundreds of convicted prisoners were innocent. Yet, throughout that time, the Supreme Court has shielded prosecutors from claims that they hid evidence that could have revealed the truth and has been reluctant to give prisoners a right to reopen old cases.

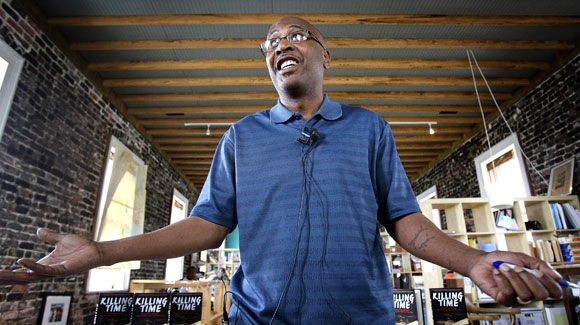

By a 5-4 vote Tuesday, the high court threw out a jury verdict won by John Thompson, (above) the Louisiana man who had sued the New Orleans district attorney after he spent 14 years on death row for crimes he did not commit. In the past, the court has shielded individual prosecutors from being sued, even if they deliberately framed an innocent person. Last week's decision protects a district attorney's office from being sued for a series of errors that sent an innocent man to prison.

Advocates for the wrongly convicted denounced the decision. Prosecutors have "enormous power over all of our lives," said Keith Findley, president of the Innocence Network, yet "no other profession is shielded from this complete lack of accountability."

In Thompson's case, at least four prosecutors knew of the blood test, eyewitness reports and other evidence that, once revealed, showed they had charged the wrong man.

"When this kind of conduct happens and it goes unpunished, it sends a devastating message throughout the system," said Sherrilyn Ifill, a University of Maryland law professor. "It means more of these incidents will happen."

Lawyers who represented the wrongly convicted also said they were shocked that Scalia would cite the 1988 case of Arizona vs. Larry Youngblood to bolster his opinion. More than a decade ago, after Scalia and the other justices sent Youngblood back to prison, new DNA tests revealed he was innocent.

Carol Wittels, the Tucson lawyer who fought to free Youngblood, said she found it "astounding" that the court would still cite the case as a precedent. "It was a horrible decision then, and I can't believe they are still citing it, since so many people have been cleared with DNA evidence since then," Wittels said in a telephone interview.

Justice Clarence Thomas delivered last week's decision reversing the $14-million jury verdict for Thompson. Scalia wrote a separate opinion citing the Youngblood case, which came to the court in Scalia's second year on the bench.

The case began when a young boy was abducted outside a church carnival and brutally raped. He said his assailant was a black man with a bad right eye. Youngblood was a black man from the Tucson area who had a bad left eye. The boy picked him from a photo lineup.

But in a crucial mistake, the police failed to refrigerate the boy's clothing and several swabs. Though Youngblood protested his innocence, forensic testing in the early 1980s could not determine whether he was or was not the perpetrator.

After two trials, he was convicted, but a state appeals court ordered him freed because the police had "permitted the destruction of the evidence" he needed to prove he was not guilty.

But the Supreme Court ruled the police and prosecutors had no duty to "preserve potentially useful evidence" for a defendant. The vote was 6 to 3, with Scalia in the majority.

Youngblood was sent back to prison in 1993, served his full term until 1998, and was later arrested because he had failed to register as a sex offender.

In 2000, the Tucson Police Department agreed to conduct DNA tests that were more sophisticated than what had been available earlier. They pointed to the true perpetrator, Walter Cruise, a black man with a bad right eye who was then in a Texas prison serving time for two sex assaults against children. He pleaded guilty to the Arizona rape.

In last week's opinion, Scalia cited the Youngblood case in arguing that prosecutors are not required to offer all the evidence that might free a defendant. "We have decided a case that appears to say just the opposite," he wrote. "In Arizona v. Youngblood, we held that unless a criminal defendant can show bad faith on the part of the police," the defendant does not have a right to obtain all "potentially useful evidence."

There is no duty under the Constitution for prosecutors to turn over test results "which might have exonerated the defendant," Scalia said, quoting the Youngblood decision. Only Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. joined his separate opinion.

University of Virginia law professor Brandon Garrett, who has studied hundreds of cases of wrongly convicted people, said he found it astonishing that Scalia would assert that prosecutors were allowed to conceal the results of the lab test.

"That's a ridiculous suggestion. They knew the lab results were powerful evidence that could be exculpatory," said Garrett, meaning it could prove innocence. "It's ironic he would say such a thing by citing the Youngblood case, where the defendant was innocent."

Youngblood died in 2007 without receiving any compensation for his years in prison, Wittels said. "I think he would be outraged to know they are still citing his case," she said.