New Study that Analyzed 98 Million US Traffic Stops Concluded that Police Stop Black Drivers and then Search Their Cars at 2 Times the Rate of Whites

/From [HERE] A new study by researchers from the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research has found that Black drivers are more frequently searched during traffic stops without finding contraband compared to white drivers. The findings, published in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology, highlight a pervasive bias in policing across multiple states and counties.

Analyzing 98 Million Traffic Stops Across the U.S.

Maggie Meyer, a doctoral candidate in psychology, and Richard Gonzalez, director of the Research Center for Group Dynamics at ISR and professor of psychology, analyzed data from 98 million traffic stops using the Stanford Open Policing Project database. They examined traffic stops in 14 state police departments and 11 local law enforcement departments between 1999 and 2017.

The researchers found that innocent Black drivers were likely to be searched about 3.4 to 4.5 percent of the time, while innocent white drivers were likely to be searched about 1.9 to 2.7 percent of the time.

“We show that there’s this pervasive bias in multiple states and multiple counties across different stop and search reasons that we need to understand,” said Meyer. “We’re not the first people to find racial bias in policing and we won’t be the last, but hopefully, this gives a clear place to intervene.”

Developing the Overlapping Condition Test to Account for Missing Data

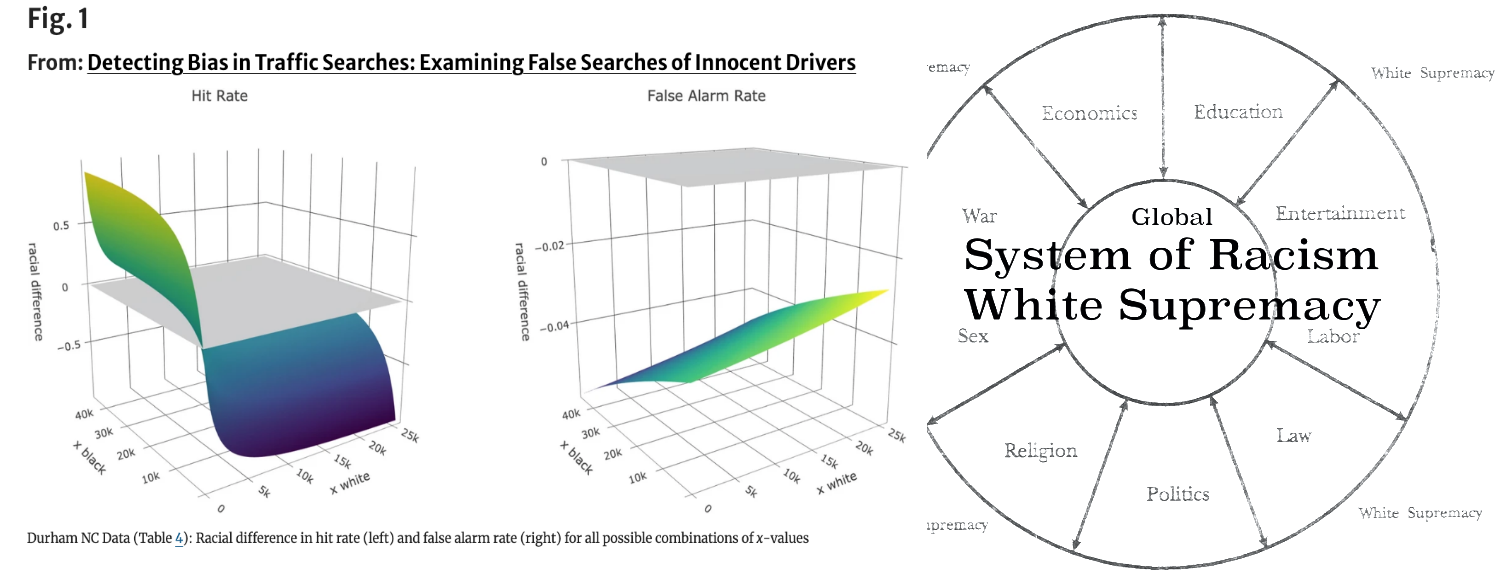

To account for the unknown information about whether drivers who weren’t searched held contraband, the researchers developed the Overlapping Condition Test. This test is based on a standard descriptive tool in statistics called a 2×2 table, which allows researchers to jointly evaluate a decision and an outcome using hit rates and false alarm rates.

The researchers explored the possible values of the missing information and found that even without knowing the actual values, the bias was still present.

“It’s analogous to presidential elections with the electoral college. An election can be called because one candidate already has enough electoral votes to win, even though all of us haven’t been counted,” Gonzalez said. “Even if those uncounted votes went for the other candidate, one candidate has already got it in the bag.”