From [HERE] When police officers in Paterson, N.J., responded to a 911 call in March from a man in the midst of a mental health crisis, they found someone they knew well.

The man, Najee Seabrooks, had worked for years to reverse a spike in shootings in Paterson, the state’s third largest city, by building friendships with gunshot victims and persuading them not to retaliate against their attackers.

But now, Mr. Seabrooks, 31, had barricaded himself in a bathroom. The police arrived in riot gear and trained their guns on the bathroom door. After a four-hour standoff, Mr. Seabrooks emerged with a knife. The police shot and killed him. Soon the city erupted — not for the first time — in bitter protests.

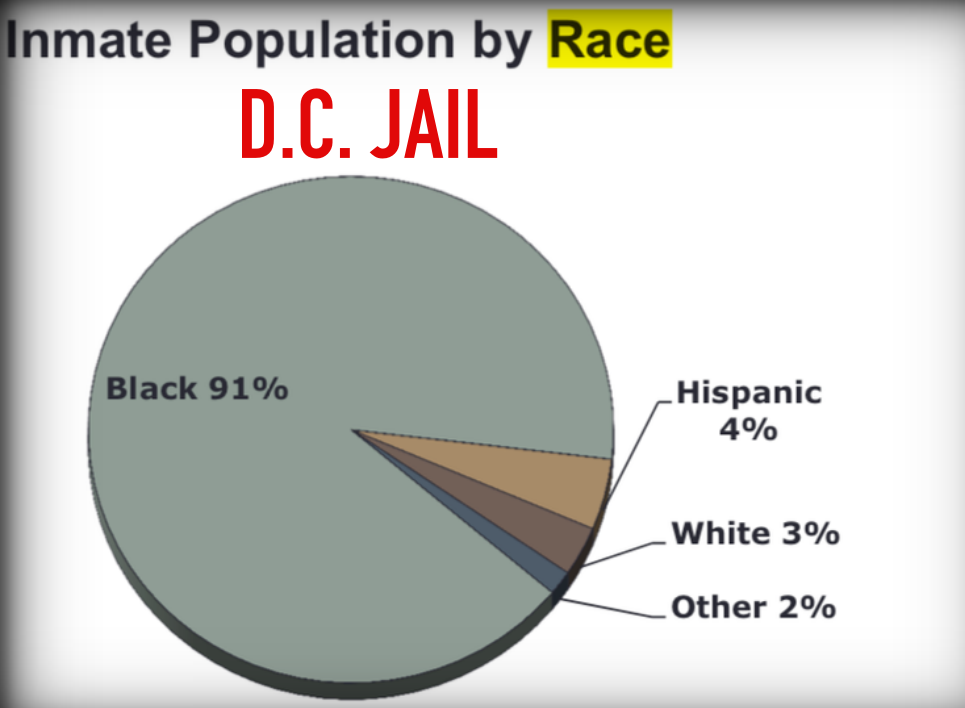

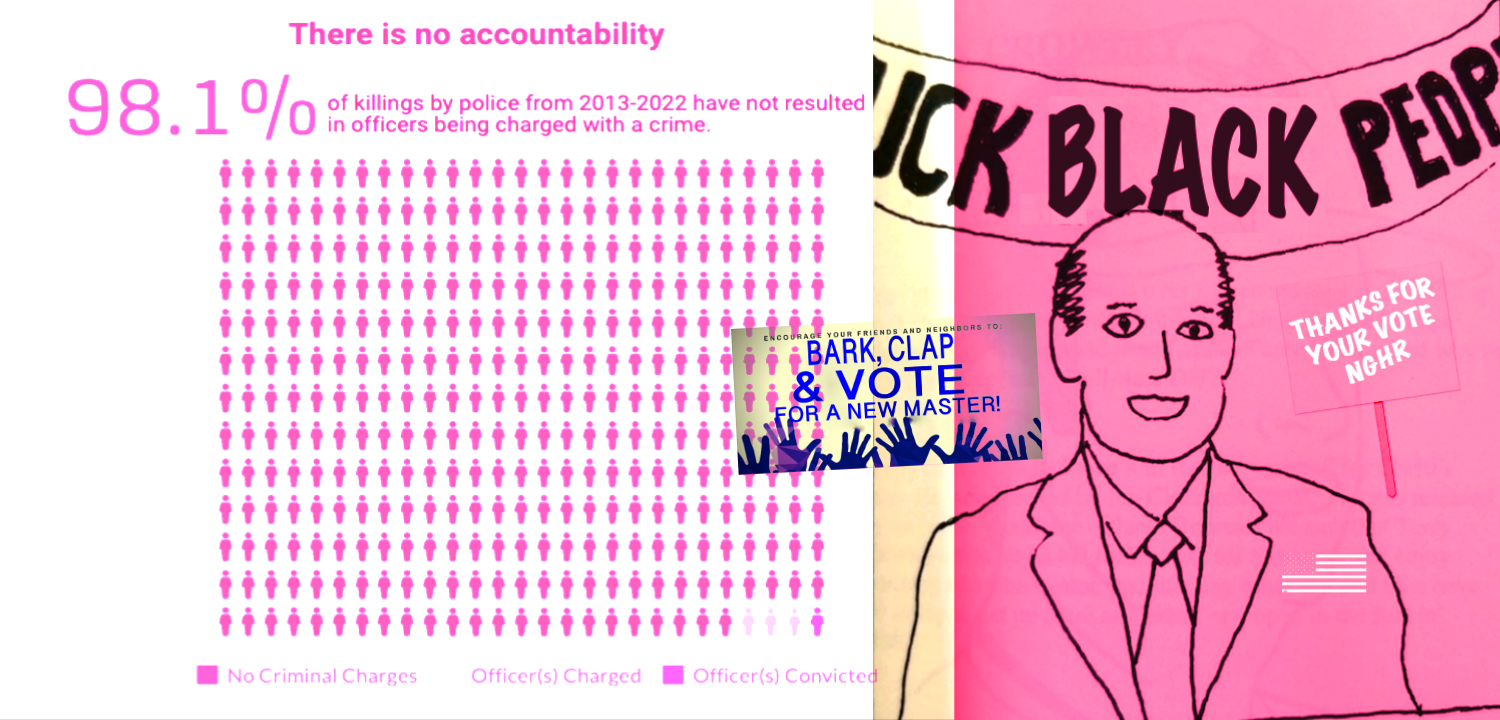

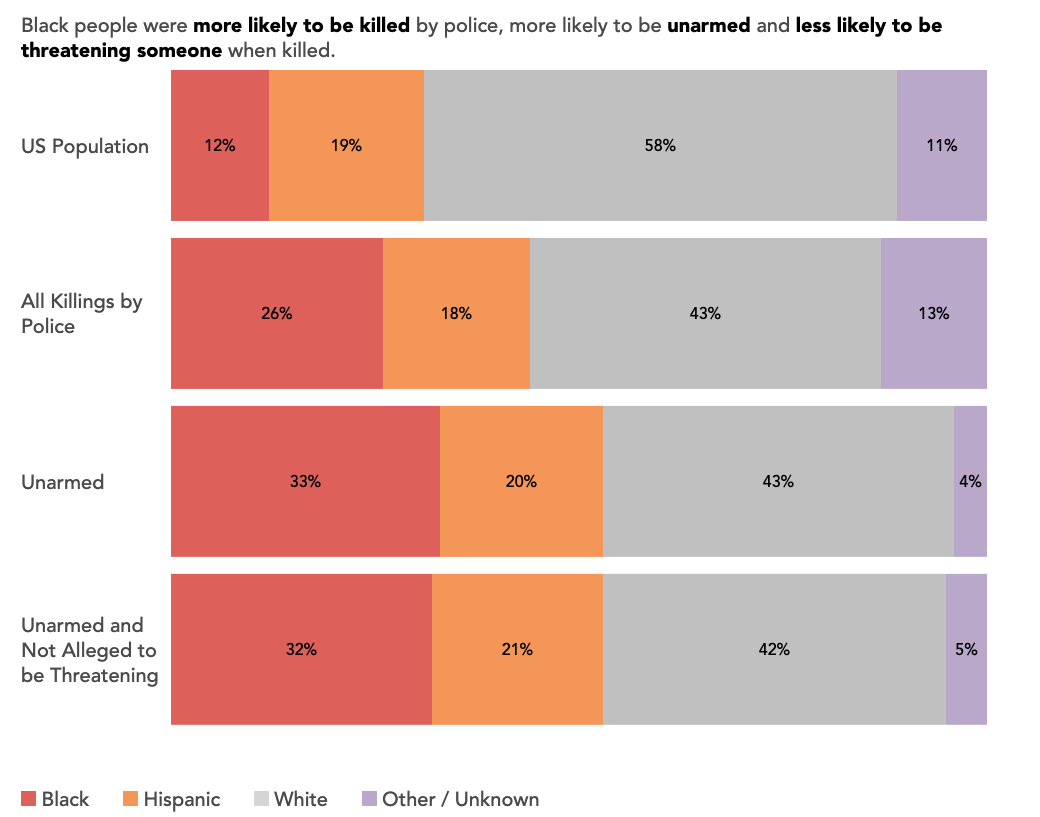

Police officers in Paterson have robbed, beaten, shot and killed scores of Black men, earning the department a reputation as one of the most troubled in New Jersey. Between 2018 and 2020, the city’s Black residents, who make up about a quarter of the population, were the subject of 57 percent of the police department’s 600-plus uses of force, according to an investigation last year by the Police Executive Research Forum, a national association of police leaders.

A police officer in Paterson was found guilty of dealing drugs from a police cruiser while in uniform. Other officers created a “robbery squad” to beat and rob people. The police have shot five people since 2019, killing four, and two more residents have died in police custody, according to state records, giving Paterson the highest number of police-involved deaths of any department in New Jersey, the news organization NJ Spotlight found in March.

Stories of police abuse in Paterson have become familiar to some New Jersey residents. But the state’s response to Mr. Seabrooks’s death was unique: Three weeks later, Matthew J. Platkin, New Jersey’s attorney general, took direct control of the police department.

The takeover, Mr. Platkin said in an interview, was a result of “high-profile misconduct by the Paterson Police Department, including a number of criminal offenses” committed by police officers. “I couldn’t go to sleep every night wondering what the next shoe to drop was going to be,” he said.

No other state gives its attorney general the power to take control of a local police department, said James E. Tierney, a former attorney general of Maine who works with the National Association of Attorneys General to train lawyers new to the position. It is only the second time that a New Jersey attorney general has exercised that power, and it is the first takeover precipitated by accusations of civil rights abuses.

“It’s a very dramatic thing to do,” Mr. Tierney said.

The takeover represents a bold attempt to answer a quandary that has long confounded cities and states across the country and boiled over in 2014, when a police officer in Ferguson, Mo., shot and killed Michael Brown: how to fix deep-rooted cultural problems and repair trust in a police department with a history of abuse, particularly in Black and Latino communities.

Mr. Platkin’s move will test whether progressive ideas about law enforcement, many of which have been adopted in other cities wrestling with the same issues, can both restore faith in the police department and tamp down crime.

“We’re taking an enlightened approach to law enforcement in ways that are evidence-based. And it’s working,” Mr. Platkin said. “There isn’t much evidence for the alternative.”

Federal civil rights investigators and officials in other states are watching Mr. Platkin’s actions in Paterson closely, said Alex del Carmen, the court-appointed special master overseeing the Puerto Rico Police Department, which has operated under a federal consent decree since an investigation in 2011 found officers used excessive force and discriminated against racial minorities. [MORE]