INTERVIEW with Juan Alberto Vázquez From [HERE] There were dozens of people who witnessed the murder of Jordan Neely — but only one, freelance journalist Juan Alberto Vasquez, recorded it and uploaded it to Facebook. By doing so, he inadvertently placed himself at the center of an ongoing debate about what bystanders should do when witnessing a violent confrontation. Curbed spoke to Vasquez about what he saw that day and what he experienced and thought about in the aftermath.

Where were you headed on the subway?

I was on my way from Brooklyn to Yonkers. I had some interviews to do up there. Right at Broadway-Lafayette, where everything took place, is where I was going to switch trains to get on the 6 and go to Grand Central and head up to Yonkers.

So when did you first notice that something was going on?

Actually, something really curious happened. I’ve made that transfer at Lafayette various times, and I know the stairs to the 6 are on one end of the platform. But I get confused about whether I should be at the front or back of the F train to be closest. So, on this occasion, working off the idea that I should be at the front, I moved train cars at every stop to make my way there. But it turns out I was wrong — the stairs are closest at the back. If I’d gotten it right, I would’ve been at the back of the train and I wouldn’t have seen anything.

So then what happened?

We stopped at Second Ave., and I saw someone running toward the doors. The door was just about to close — three, five inches away from closing — when Jordan stuck his hand between them. Can you believe that? The irony. The irony that I’d mistakenly swapped cars and the irony that if he’d gotten there a single second later, the door would have closed and he wouldn’t have gotten in.

But he stopped the door from closing and he got on the train. And he stood in the middle of the train car, and then he started yelling that he didn’t have food, that he didn’t have water. From what I understood, he was yelling that he was tired, that he didn’t care about going to jail.

Was this when you began recording?

I tried to start filming from that moment, but I didn’t because I couldn’t see anything — it was too crowded. And then I heard him take off his jacket. He bundled it up and just threw it on the floor, very violently. You could hear the sound of the zipper hitting the floor. At that moment, when he threw the jacket, the people who were sitting around him stood up and moved away. He kept standing there and he kept yelling.

When did you see the man who restrained him?

It’s at that moment that this man came up behind him and grabbed him by the neck, and I think — I didn’t see, but I think — that move of grabbing him by the neck also led him to grab Neely by the legs with his own. They both fell. And then in like 30 seconds, I don’t know, we got to Broadway-Lafayette, and they were just there on the floor. You ask how many people out of 100 would have dared to do something like that, and I think that 98 will say: “No, I would wait to see one more sign that indicates aggression.”

What happened at the subway station?

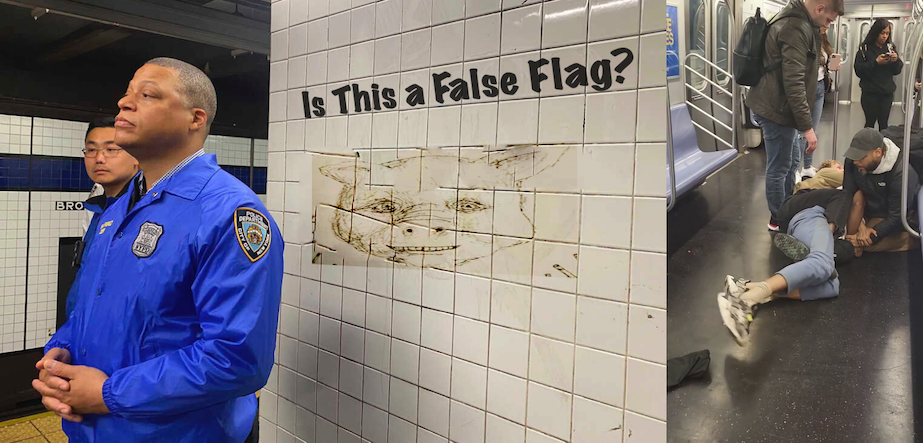

When the two doors opened, everyone rushed out, obviously afraid, because now there was an actual fight. I got out, and I was watching them on the floor with this other man helping to hold Neely down. And then there’s just this confusion over what to do, all these people standing around on the platform, and some of them were yelling, “Call the police, call the police.” There were a couple of people who approached the blond guy, they say he’s a marine, and asked him, “What’s going on?” And he told them to call the police.

Obviously, the conductor had no idea what was going on. He was just going to close the doors and keep going. But there were people who stood between the doors and said, “No! Don’t close the doors!” I went over to the conductor too, and he was saying over the speaker, “Police, police!” But obviously there weren’t any police in the station. So I went back to where the scene was. And that’s when I started to film.

So the video you posted to Facebook started at this point.

I started to film from outside, through the window of the subway car, and then went back inside. They were just lying there. Then, when Jordan tried to escape again, they rolled over, and I could see his face and his attempts to escape. Then he wasn’t moving anymore, and we were all looking at each other, like, “What’s going on? Did he faint? What happened?” I got off the train, and I filmed another 30-second video where you can see it’s the F train. In that second video, you can see Neely is lying down and two guys are standing over him — the one who grabbed him and one other man. The second guy, he wanted to help. You can see in my first video that he never touches Jordan and never tries to restrain him; he is simply trying to listen to him and trying to tell the other one not to squeeze him so hard.

I had to leave and was walking toward the 6. And at that moment, I heard the patrol cars arriving. I didn’t stay when the police arrived.

What were you thinking about when you left?

I wanted to believe he had fainted. But I wasn’t going to get involved in trying to free him or trying to help him, because you don’t know at what point you’re going to get involved in something bigger.

Why do you think this situation escalated?

Jordan wasn’t asking for money. Jordan wasn’t asking for food. He was lamenting that he didn’t have any, he was lamenting that he was fed up, that he didn’t mind going to jail, and, up until that point, everything was fine. As far as I saw, he stood still and that encouraged people to stay calm, to stay in their place. When he raised his jacket, that’s when people panicked a little and those who were around him moved. But he didn’t move either. These people who were standing between us, that couple did not move at all. They were just standing, watching him. They stayed there as if to say: “Well, until we see that there is some kind of risk.” To me, when Jordan throws his jacket, it is a way of saying: “There could be an act of violence here,” because those things do happen all the time, because just a year ago, there was a guy who went in and shot a lot of people on the train. And obviously, the marine, in the end, went too far. But the police also went too far in not arriving on time.

This is a difficult question, and I don’t know if you can really answer it, but I’m just going to ask you. Lots of people feel like you could have done something. Do you feel that way now?

I am an immigrant — my wife got a visa almost six years ago, and we came here. I was a reporter at Milenio in Mexico for 20 years. So, for a year, I was here learning a little English, taking care of my children. I kind of became Mr. Mom. And eventually I started doing little freelance jobs. And look, as an immigrant, we are in a situation that sometimes ties us down. We do not have the same rights. People always advise that you not get involved. Why get involved in something that could cause problems with your immigration status? You know that here in the U.S., if you so much as miss a stop sign, it could become a reason to be deported or not granted a permit.

On the other hand, at some point in all this, I had the impulse to do something, whether to ask the other guy to let him go or whether to help Jordan escape or whether to say: “Let him go and between us, we can control him.” But, at some point I also got nervous, which is why I went in and out of the train car. And when I came back, I saw that there were two other people involved. Then I said to myself: “Well, let them help and let them try to resolve the matter.”

But I don’t regret it. I regret giving my name to the New York Post, because from then on, there was all this persecution by the media. I mean, I should have given them the interview but without my name. Now it’s too late. They already know who I am. People have even come and knocked on my door.

Ultimately, I wasn’t thinking that anybody was going to die. I can’t have regrets for something I didn’t know. [MORE]